SKILLS

Attribute of Skills

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua

About

Overview of the attribute. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

"The framework, tools, and language of system dynamics should be accessible to all. Anyone can do this at some level, and everyone should try!" — Barry Richmond

The SysQ Mindset (or Aim) is important, but it’s not enough on its own to create effective and powerful strategies to tackle tough, complex, and chaotic issues. Just saying, “Let’s try to understand the structure causing the problem we want to solve” without coming up with new ways to make sense of the world is like knowing you’re drowning but not knowing how to swim. As Einstein said, “We can’t solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Others might say, doing the same things over and over again (with the same thinking) is the definition of insanity.

THE THINKING APPLIED TO THE US COUNTERINSURGENCY STRATEGY

Excerpt From a Famous — Yet Poorly Titled — New York Times Headline

We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Powerpoint

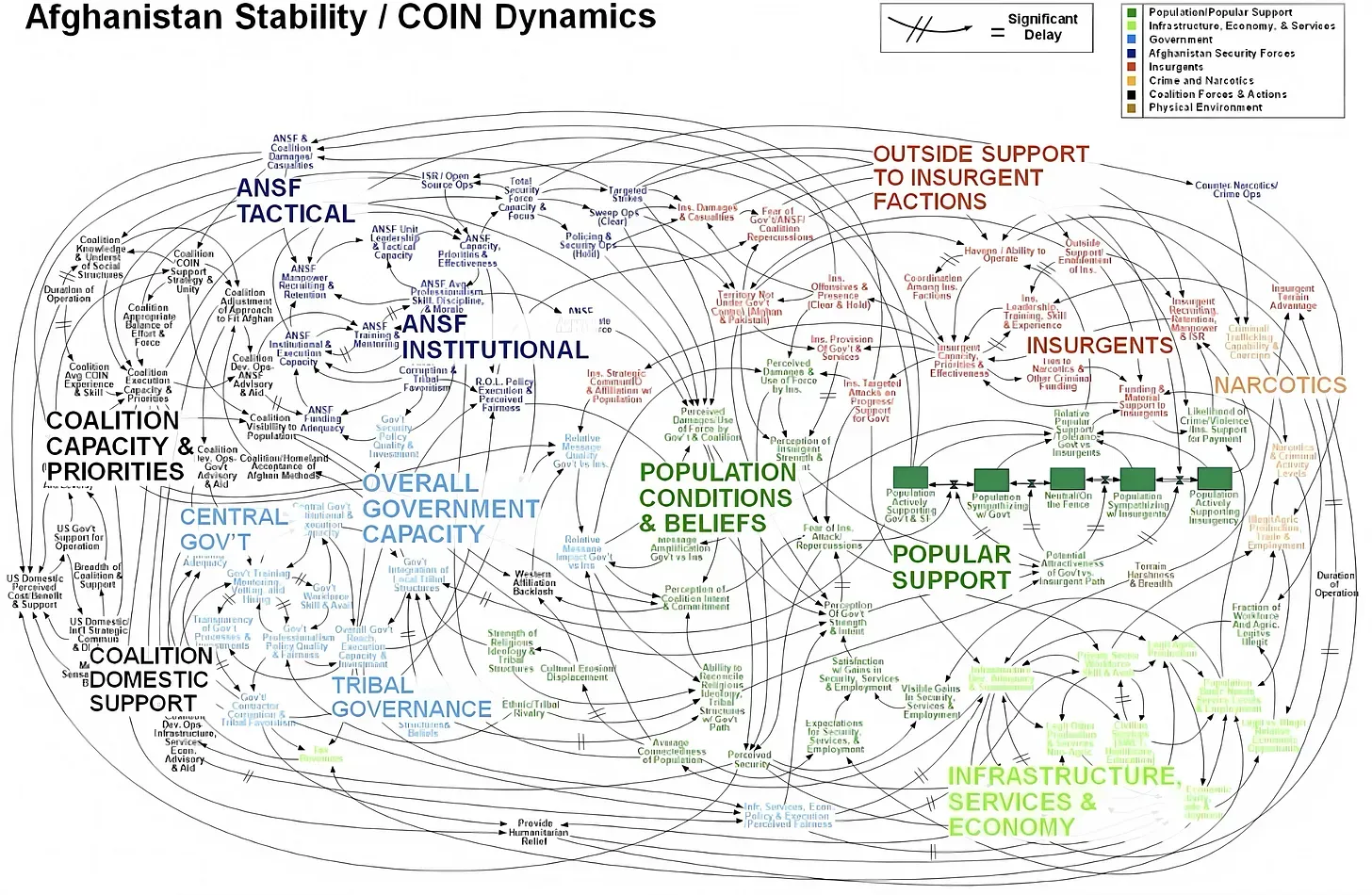

Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, the leader of American and NATO forces in Afghanistan, was shown a PowerPoint slide in Kabul last summer that was meant to portray the complexity of American military strategy, but looked more like a bowl of spaghetti.

“When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war,” General McChrystal dryly remarked, one of his advisers recalled, as the room erupted in laughter.

The slide has since bounced around the Internet as an example of a military tool that has spun out of control. Like an insurgency, PowerPoint has crept into the daily lives of military commanders and reached the level of near obsession. The amount of time expended on PowerPoint, the Microsoft presentation program of computer-generated charts, graphs and bullet points, has made it a running joke in the Pentagon and in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“PowerPoint makes us stupid,” Gen. James N. Mattis of the Marine Corps, the Joint Forces commander, said this month at a military conference in North Carolina. (He spoke without PowerPoint.) Brig. Gen. H. R. McMaster, who banned PowerPoint presentations when he led the successful effort to secure the northern Iraqi city of Tal Afar in 2005, followed up at the same conference by likening PowerPoint to an internal threat.

“It’s dangerous because it can create the illusion of understanding and the illusion of control,” General McMaster said in a telephone interview afterward. “Some problems in the world are not bullet-izable.”

In General McMaster’s view, PowerPoint’s worst offense is not a chart like the spaghetti graphic, which was first uncovered by NBC’s Richard Engel, but rigid lists of bullet points (in, say, a presentation on a conflict’s causes) that take no account of interconnected political, economic and ethnic forces. “If you divorce war from all of that, it becomes a targeting exercise,” General McMaster said.

Commanders say that behind all the PowerPoint jokes are serious concerns that the program stifles discussion, critical thinking and thoughtful decision-making. Not least, it ties up junior officers — referred to as PowerPoint Rangers — in the daily preparation of slides, be it for a Joint Staff meeting in Washington or for a platoon leader’s pre-mission combat briefing in a remote pocket of Afghanistan.1

As I mentioned, I think the title of this article is a bit misleading. It’s not really a problem with PowerPoint, although I’ll admit that it can make meetings a bit dull. The issue is with the type of “systems” analysis that’s been done.

While it’s a good attempt to map out the system, it doesn’t follow the basic principles of focusing only on the parts that are responsible for the behavior. It’s like mapping every color in the slinky shown earlier and including all the other details that don’t really matter. When we’re trying to solve complex problems, we need to simplify the process of mapping the structure and use some additional SysQ Thinking Skills.

THINKING SKILLS

To truly apply the mindset of SysQ, we need to think beyond the surface-level behaviors and delve into the underlying structures that drive them. This requires developing some rarely used systemic thinking skills.2 We must shift up from the traditional thinking we apply to problem solving into this higher order thinking. Some types of shifts in thinking include shifting from…

EVENT Thinking — We focus on the latest or most newsworthy event.

➡︎ DYNAMIC Thinking — We shift to seeing how that event is part of a longer term trend. This helps us more clearly see what structural forces might be driving that pattern.

TREE Thinking — We focus individually on each silo in the organization, each department in the division, each sector in society, each country around the world — the equivalent of tree-by-tree thinking.

➡︎ FOREST Thinking — We try to understand how each silo interacts within the organization and even outside it. This interconnected web of departments, divisions, offices, silos, and sectors — the forest — is responsible for larger system behavior.

CORRELATIONAL Thinking — We use regression and correlational analysis to propose causality. Or use anecdotal evidence of when I see this happen something else happens — without a clear and rigorous causal theory.

➡︎ OPERATIONAL Thinking — A former colleague read an esteemed academic paper on US dairy policy that was prescribing potential strategies to increase production. The analysis included economic indicators like interest rates, feed prices, farming expenses — but despite having high statistical confidence, the analysis left out the one system component essential for production. Cows. Only a model that includes cows can be operational. Only operational models create clarity on levers. Yet we often create strategies based on non-operational thinking as useless as a dairy model without cows.

LINEAR Thinking — We assume working more hours will complete more work, hiring more people will impact client satisfaction, hiring a consultant will improve our capacity, and an endless stream if IF THIS THEN THAT.

➡︎ FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking — The world works with feedback loops. For example, there’s a feedback loop where more hours worked builds burnout, less completion, more hours, and more burnout. A nasty feedback loop begins to dominate as a vicious cycle. Feedback loops drive the complex dynamic behaviors experienced in the real world and must be included in our strategies and decisions.

MEASUREMENT Thinking — A commonly held belief is to make decisions only using data that we can measure precisely and represent numerically in our models. Production can be included. Burnout can’t.

➡︎ QUANTITATIVE Thinking — Anyone think Burnout doesn’t determine production? Unless you do believe it has no impact, then you know any model excluding it to be wrong. Even if unmeasured, it can still be quantified — even if anecdotally — ranging from 0-100. 0 means everyone is super relaxed; 100 means they are immobilized from burnout.

APPLYING SOME OF THE SYSQ THINKING SKILLS TO THE COUNTERINSURGENCY STRATEGY

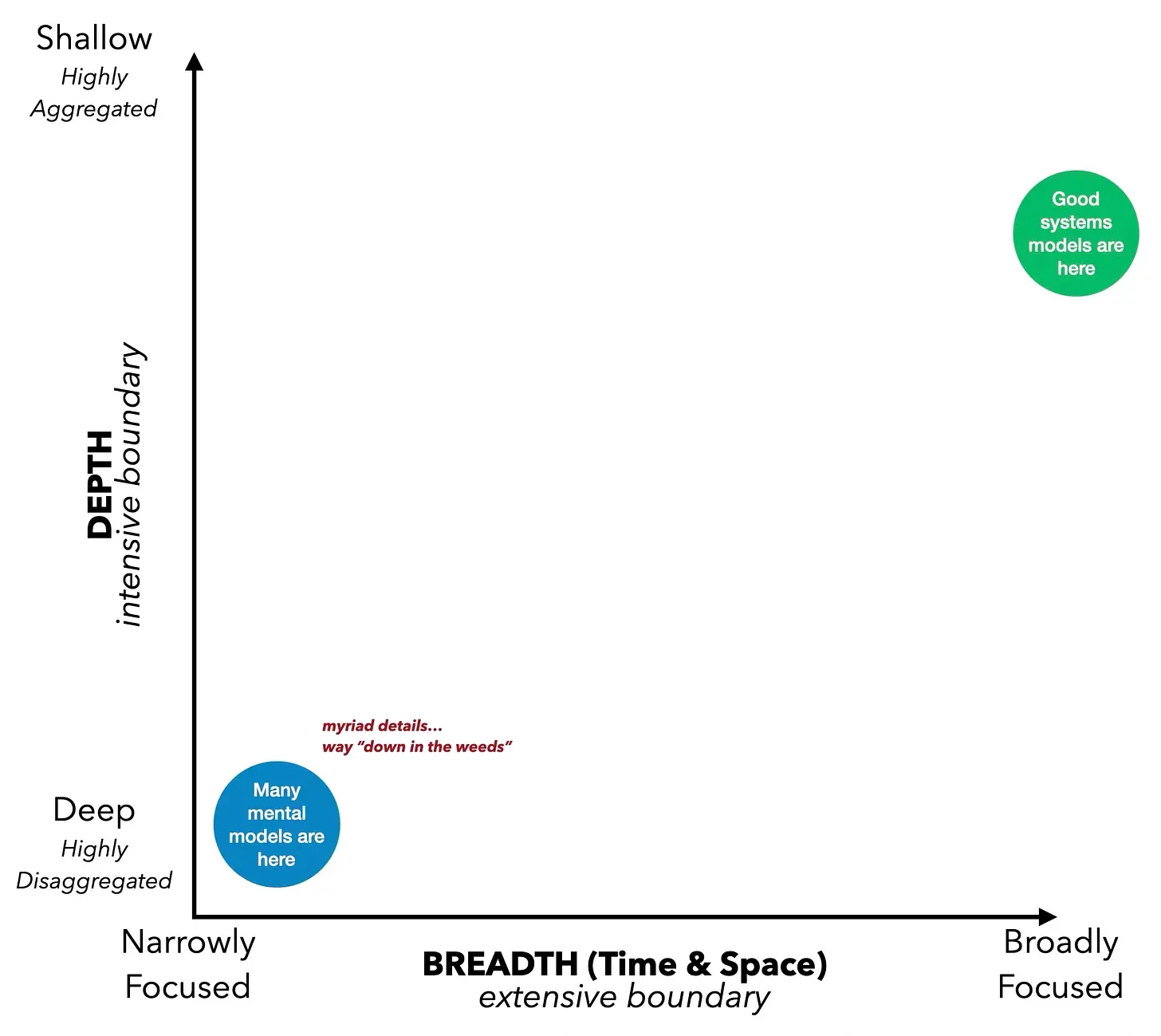

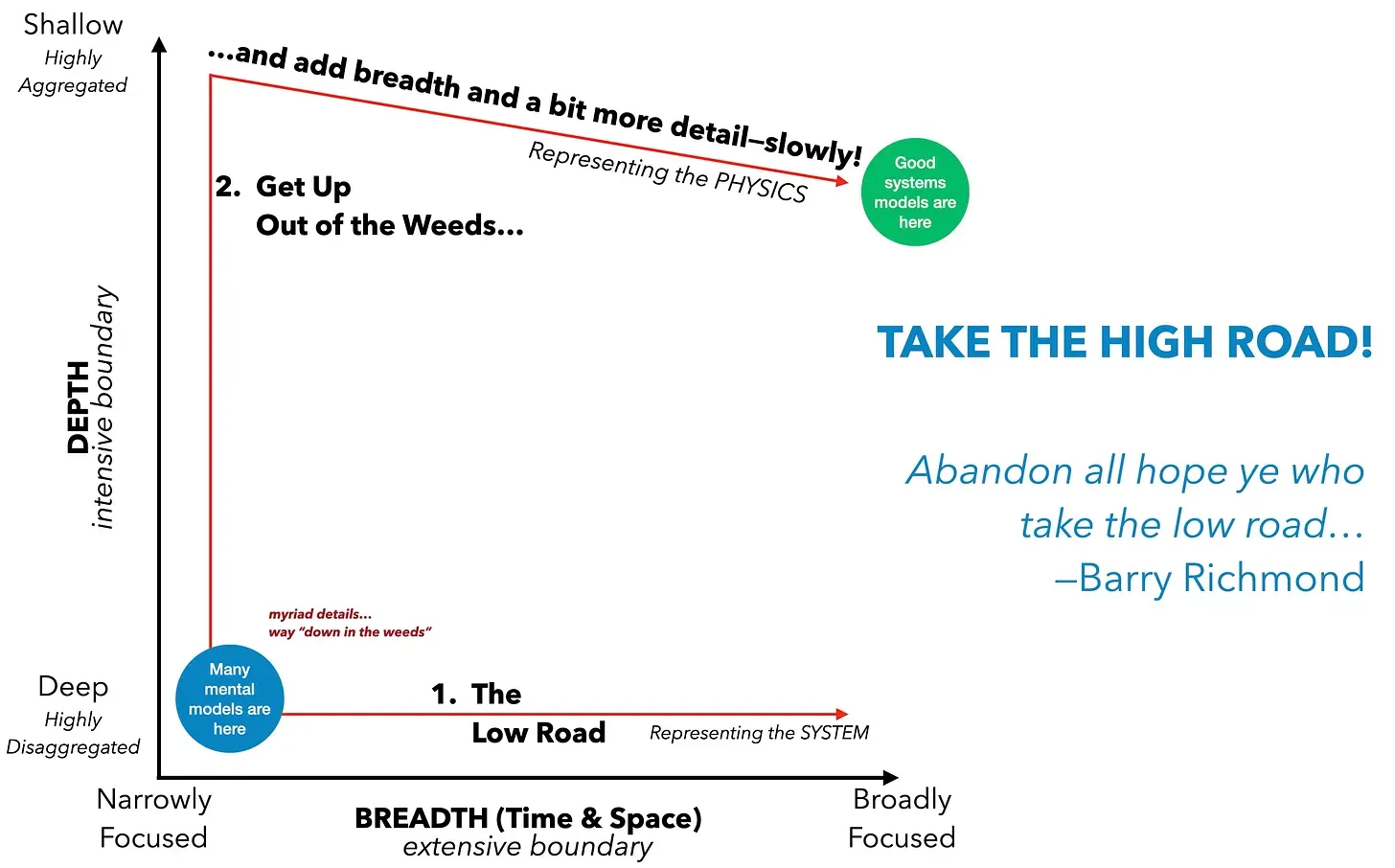

Let’s explore how the thinking skills mentioned here can be applied to the US Afghanistan counterinsurgency strategy. We’ll use an analysis by Barry Richmond, the mastermind behind many of the SysQ thinking skills, and further explained by my colleague, Steve Peterson, in The Systems Thinker.3

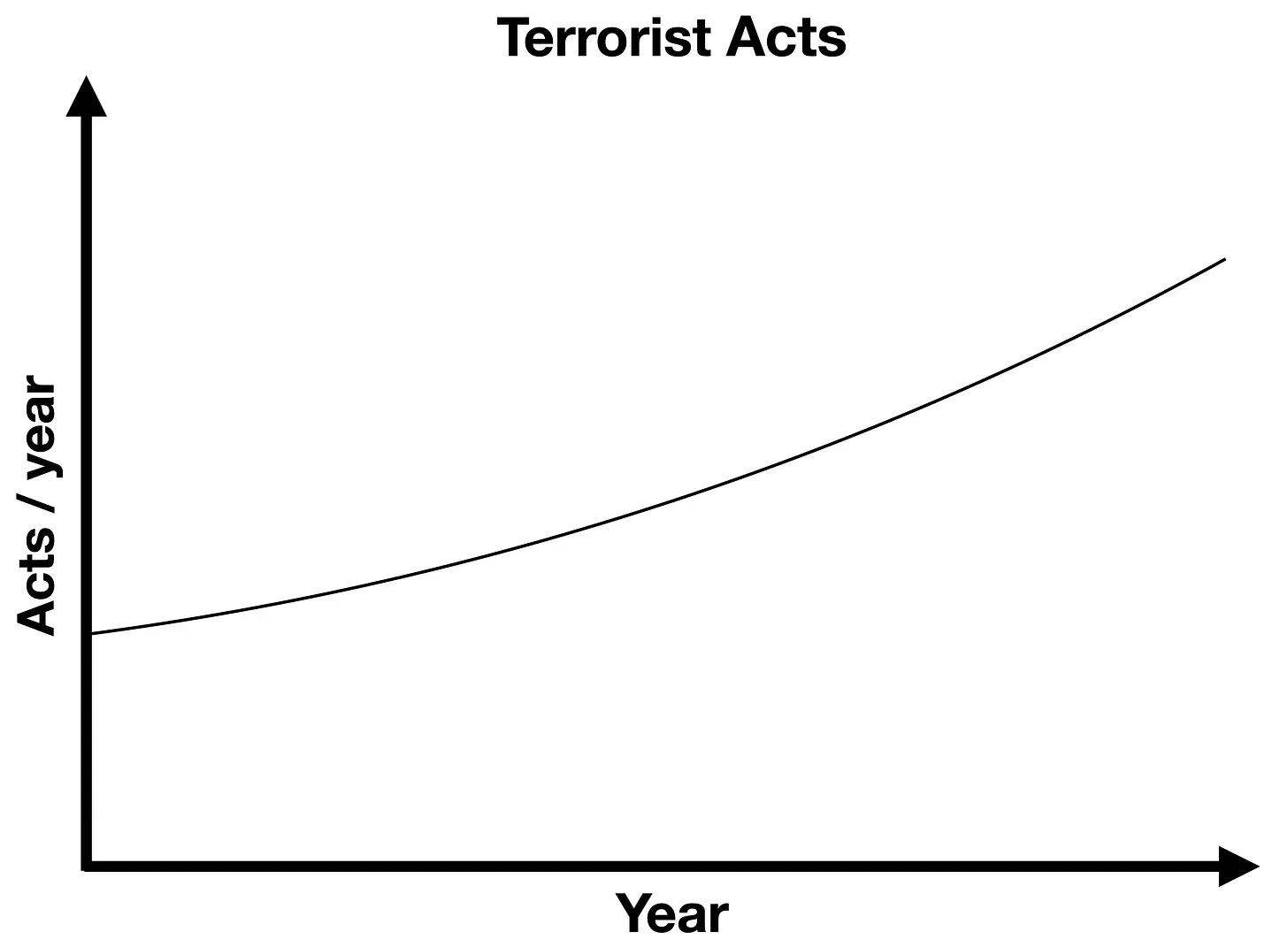

Instead of looking at the latest terrorist event as something to respond to in isolation — where a strategy would be to hunt down those responsible and bring to justice — DYNAMIC Thinking would suggest it’s important to look at terrorist acts as a trend over time

Further, FOREST Thinking would ensure that the activity of terrorism wasn’t just localized to a region within Afghanistan. Instead it would look at such activity over the breadth of the country…and perhaps the network extends even outside the borders.

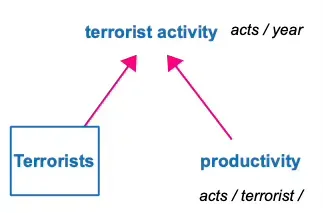

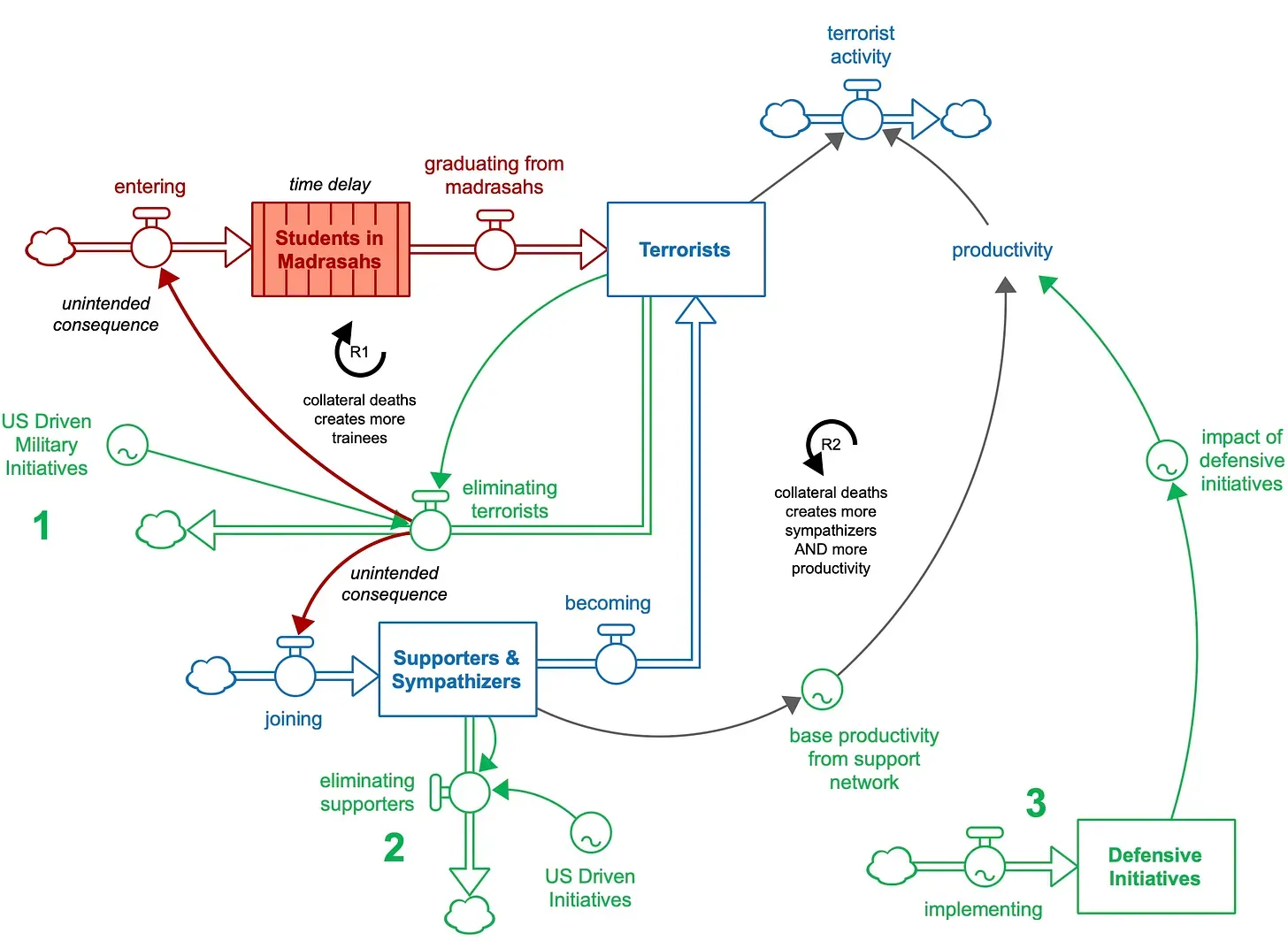

Having used SysQ to frame up the issues to be able to find leverage, we can apply OPERATIONAL Thinking. The number of terrorist acts occurring over a year is generated by two variables: the number of terrorists and their productivity (terrorist acts / terrorist / year). By making it operational, it becomes clear there are only two levers (places) to apply an intervention to reduce terrorist activity. Reduce the number of terrorists and or reduce their productivity — their terrorist acts/terrorist/year. That’s it. All solutions will be designed to work on one or both of these levers.

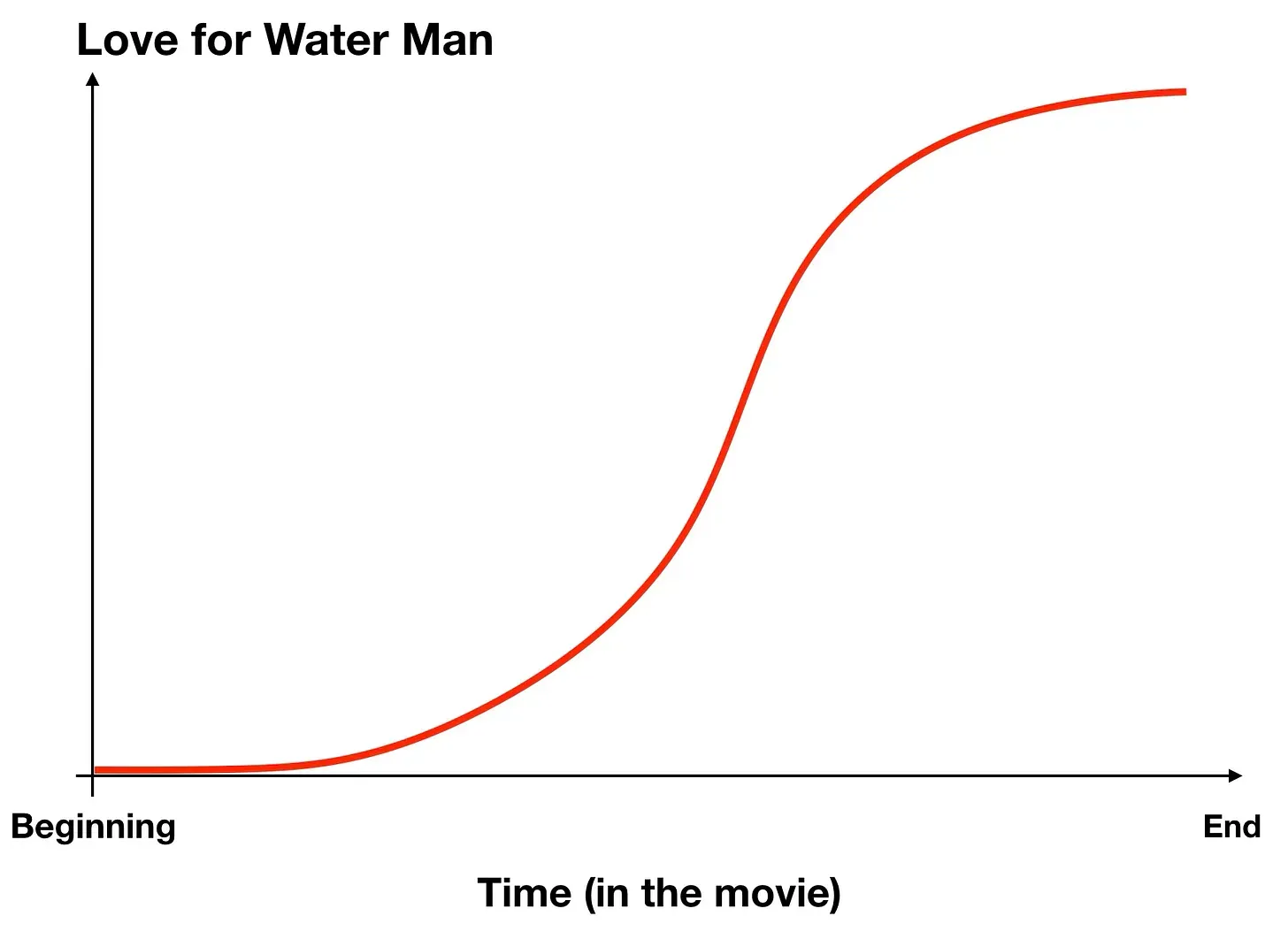

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.

Finally, although in our simplistic view of the world, it would be awesome for our actions to only impact the intended target, we just learned with FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking that’s often not the case. In fact, by applying RIPPLE EFFECT Thinking we can see that not only would killing terrorists likely lead to more terrorists signing up. Killing innocent civilians can also lead to more sympathizers, who can increase terrorist productivity. They might provide financial resources, hide or house terrorists, or share intelligence that helps them.

In our organizations, we often think that lowering prices will boost sales. But here’s the thing: sometimes, when sales go up too high, customers aren’t happy, and sales start to drop. It’s like a balancing act.

In our communities, we usually think that the only way to stop crime is to have more police. But there are other things that can help too, like housing, unemployment, access to support for substance abuse, and even a sense of community and belonging. We need a different way of thinking, like the FOREST approach, to find effective solutions.

There are many thinking skills that are part of what I call Systemic Intelligence, which is like a superpower for thinking. These skills can help us in all sorts of areas of life. But to make better strategies and find ways to make things work, we need to use them in a process and with some tools.

SYSQ THINKING SKILLS

If you’re looking to learn practical ways to build any or all of these thinking skills, you’ve come to the right place. This substack will dive deep into each skill. There’s even a section dedicated to just the skills. And guess what? The best way to build these skills is by using some of the SysQ Tools as you learn (using the SysQ Process). Keep an eye out for articles tagged with Thinking Skills to see how they’re applied in real-world examples.

Everyone has some level of these skills, but the goal of this substack is to help us all improve and strengthen them so we’re ready to tackle the toughest problems life throws our way.

1

Bumiller, E. We Have Met the Enemy and He Is PowerPoint, New York Times (April 26, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/27/world/27powerpoint.html

2

Barry Richmond first proposed 7 Systems Thinking Skills of a Systems Thinker in The Thinking in Systems Thinking: How Can We Make It Easier to Master? The Waters Center for Systems Thinking has since added to those skill to create the 14 Habits of a Systems Thinker.

3

Peterson, S. Applying System Dynamics To Public Policy: the Legacy of Barry Richmond. The Systems Thinker. https://thesystemsthinker.com/applying-system-dynamics-to-public-policy-the-legacy-of-barry-richmond/

Additional Resources

Books

Book title as link | Description

Articles

Article title as link | Description

Online Resources

Resource title as link | Description

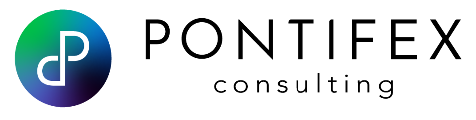

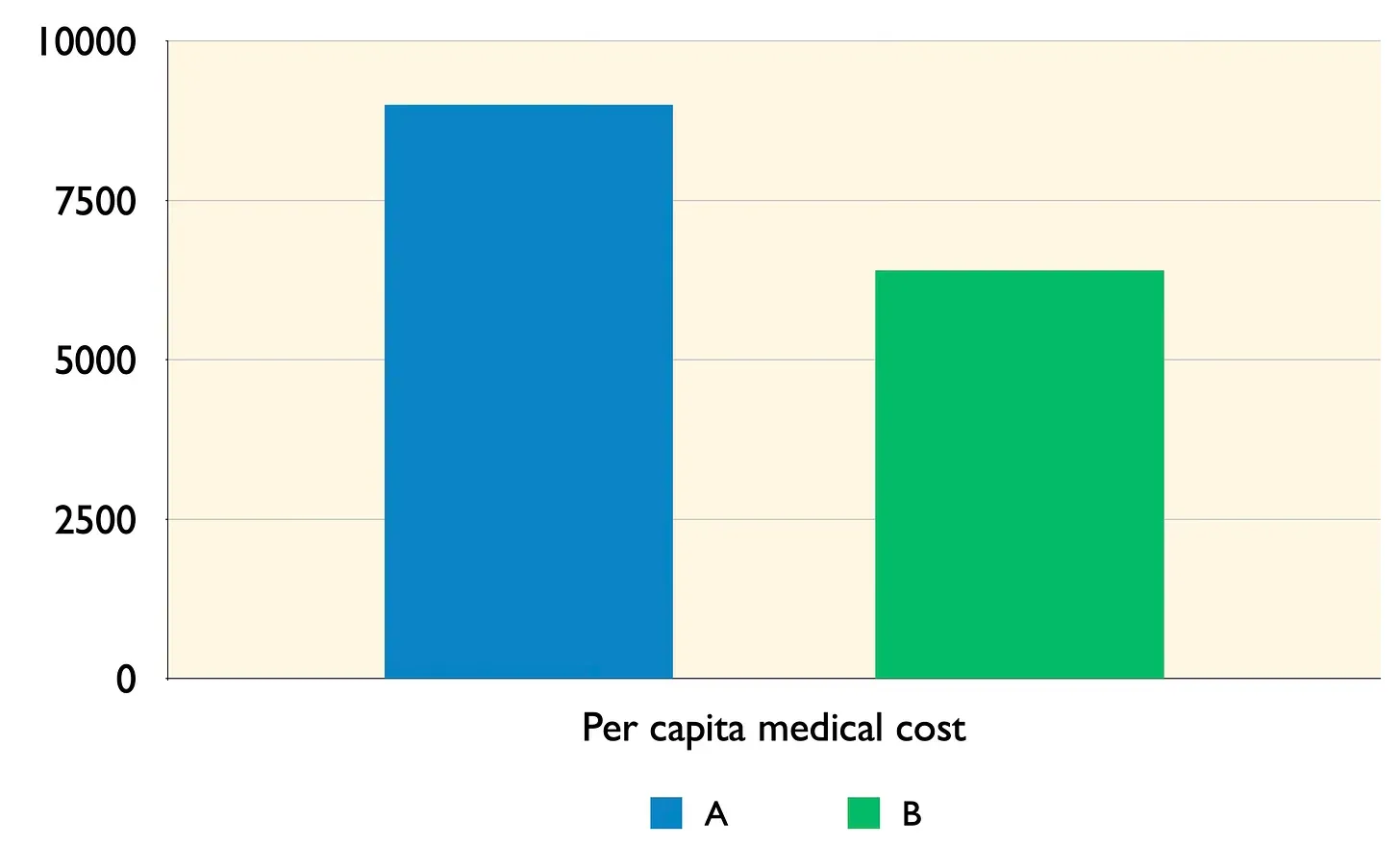

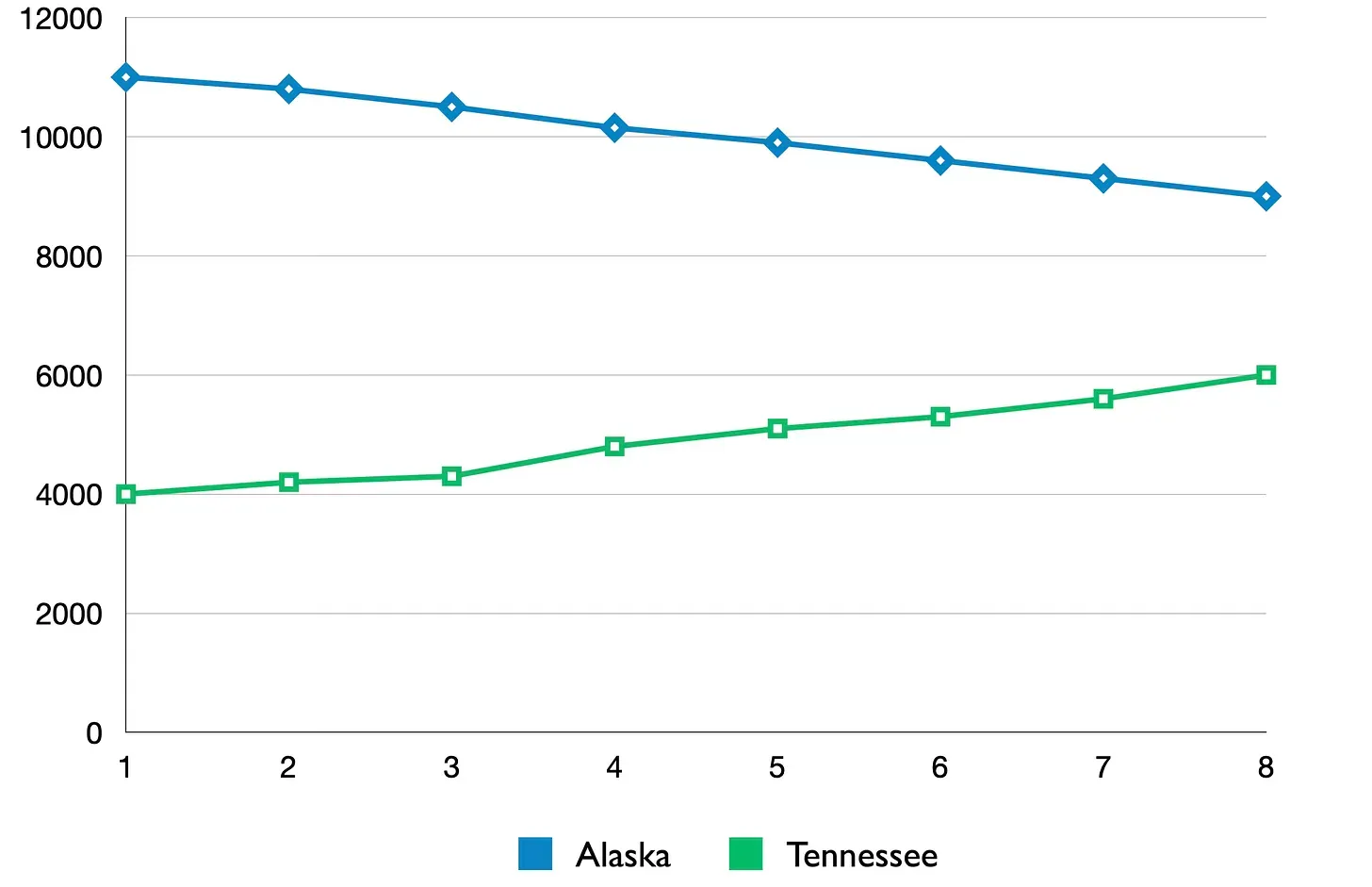

Bad, right? Worried?

Bad, right? Worried?

Now how do you feel?

Now how do you feel?

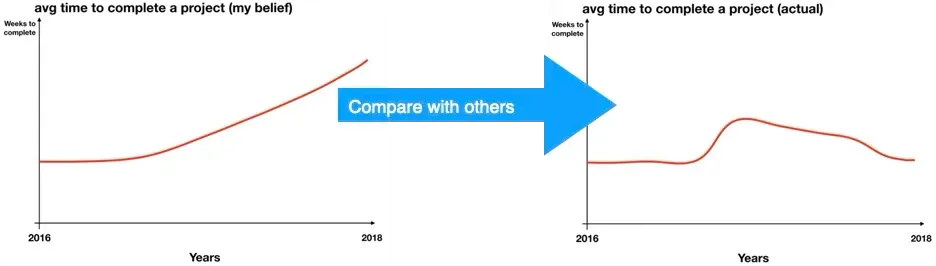

The High Road process involves sharing the initial “starter map” or “starter model” with others. Does it provide a clear explanation of why the performance issue is occurring? What changes or additions are needed? Make small adjustments and share the updated model for testing.

The High Road process involves sharing the initial “starter map” or “starter model” with others. Does it provide a clear explanation of why the performance issue is occurring? What changes or additions are needed? Make small adjustments and share the updated model for testing.