"We count by years, but we live by days. Rightfully, we should do both by seasons." — Ivan Doig, Dancing at the Rascal Fair

YOU’RE ON A COMPANY’S EXECUTIVE TEAM

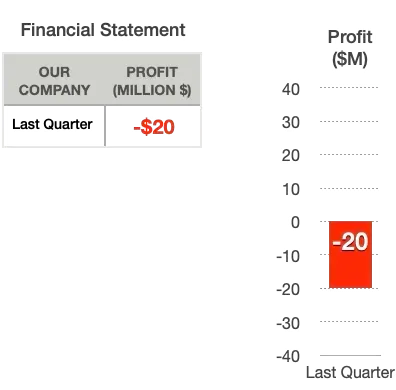

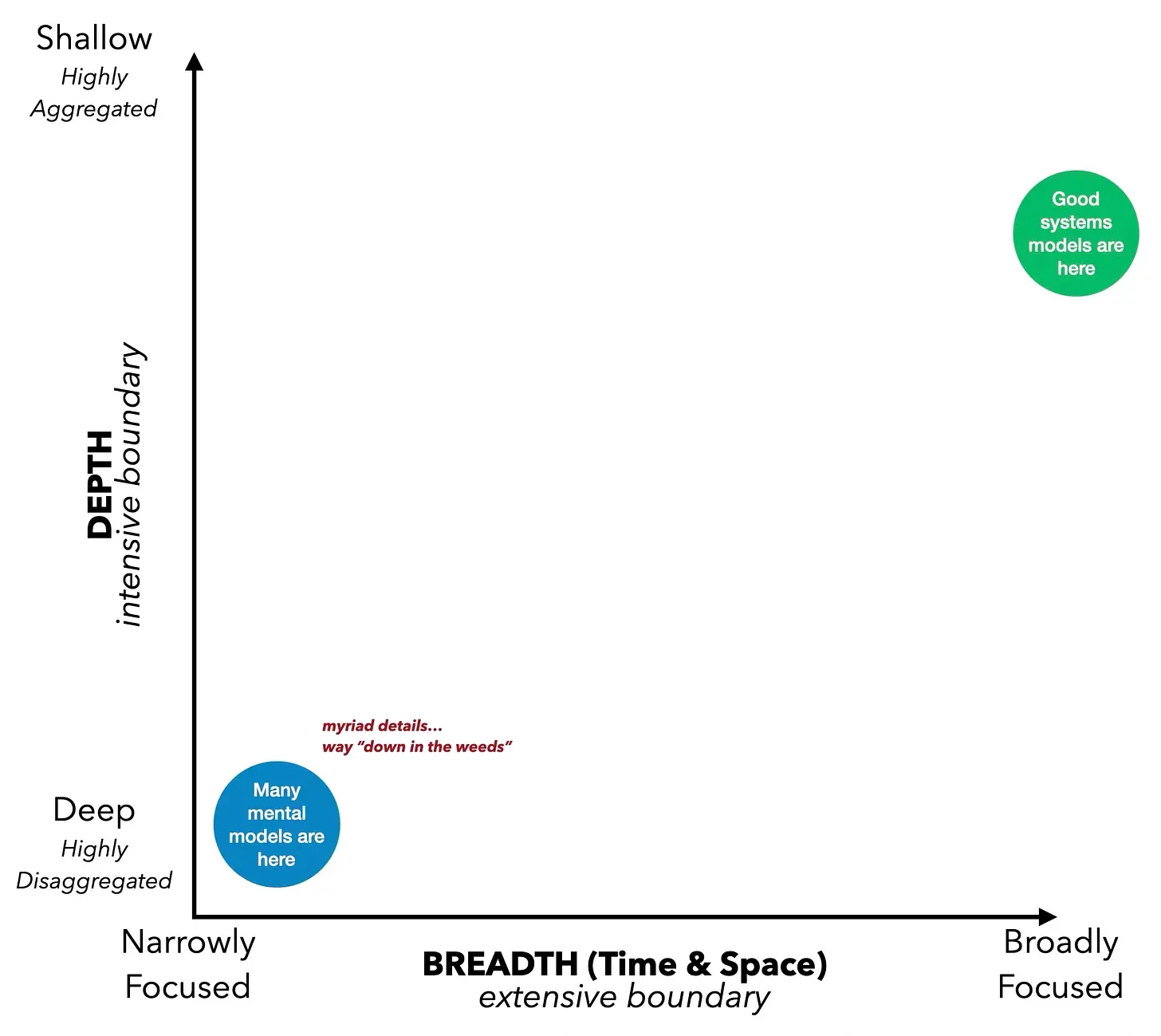

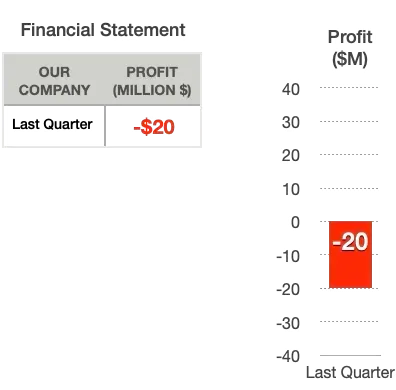

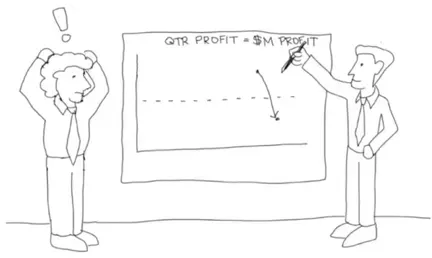

Imagine you’re on the senior executive team of a multimillion-dollar company. Last quarter’s financial statement just came out, and it’s a doozy. Your company lost several million dollars. How do you feel? Bad, right? Worried?

Bad, right? Worried?

What ideas / actions do you think the executive team would discuss and probably implement? If like most companies, you’d consider:

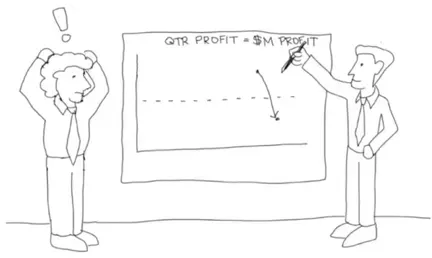

Now suppose you were shown the graph drawn below. Profit has plummeted over the past six months.

How do you feel now?

Even worse!

Why? Because it looks like things are getting worse–and rapidly!

What ideas or actions do you think the executive team would discuss and likely implement? If you’re like most companies, you might consider:

And as an individual on the team you are concerned about a few things. There is probably going to be some personnel changes on the leadership team. The CEO might be let go. The board will certainly be looking for someone to blame.

You? You are most likely improving your resume, contacting friends and colleagues in your network–spending a lot of time on LinkedIn.

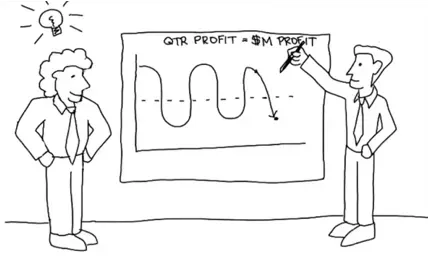

Now, suppose you’re shown this graph. Now how do you feel?

Now how do you feel?

Relieved, right? You may notice even a slight relaxing in the body now (if you were reacting at all to the exercise).

Why relieved?

Because, when viewed over a longer time horizon, the plummeting profits are part of a larger, predictable pattern.

If I asked you what type of business you’re running, you might say it’s a commodity business or more likely a seasonal business (since it has the same fluctuations at the same time each year). Maybe you’re a winter sports chain in New England, selling mostly skis and snowboards.

If it’s a seasonal business (like the winter sports chain) what solutions might you suggest?

You might suggest the following:

Closing the business in the summer months

Diversifying (sell golf clubs!)

Investing during the summer months to boost sales in the winter

Compare the solutions you would propose when analyzing the broader pattern to those you would suggest based solely on quarterly results (an event) or just a half-year’s worth of data (a small window).

The newer solutions are proactive, giving you more control and often revealing opportunities to generate additional revenue. In contrast, the reactive solutions focus on cutting costs.

The key difference between reactive and proactive solutions lies in your understanding of the business’s nature. It’s like seeing the slinky. You grasp the business’s structure, which is seasonal. Once you understand this structure, you can develop a much more effective solution tailored to your business.

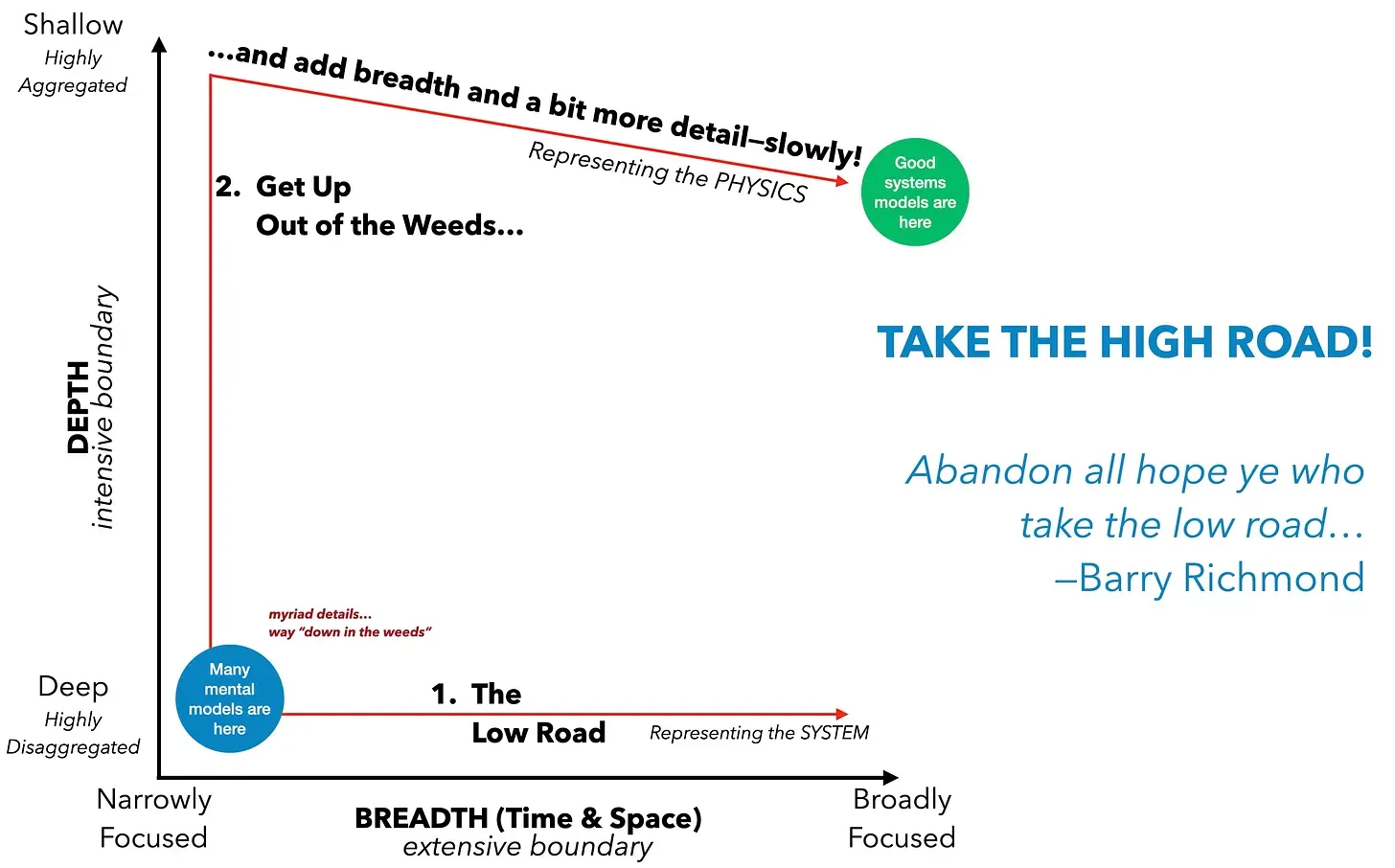

EVENT THINKING VS. DYNAMIC THINKING

From a young age, our minds naturally focus on events and behaviors that occur right in front of us, both in space and time. This is not surprising, as humans are hardwired to prioritize the immediate and the present. The ability to hyper-focus on a predator that suddenly leaps from the bushes and react swiftly has proven beneficial to our species. There’s no need to meticulously chart the long-term history of predators leaping from bushes and consuming humans; the immediate response is sufficient: run!

What sets humans apart from other animals is an additional skill: the ability to discern patterns and make predictions. This higher level of consciousness, our meta-level thinking, is essential for addressing adaptive challenges. Our mental models must also include the capacity to represent patterns and make predictions.

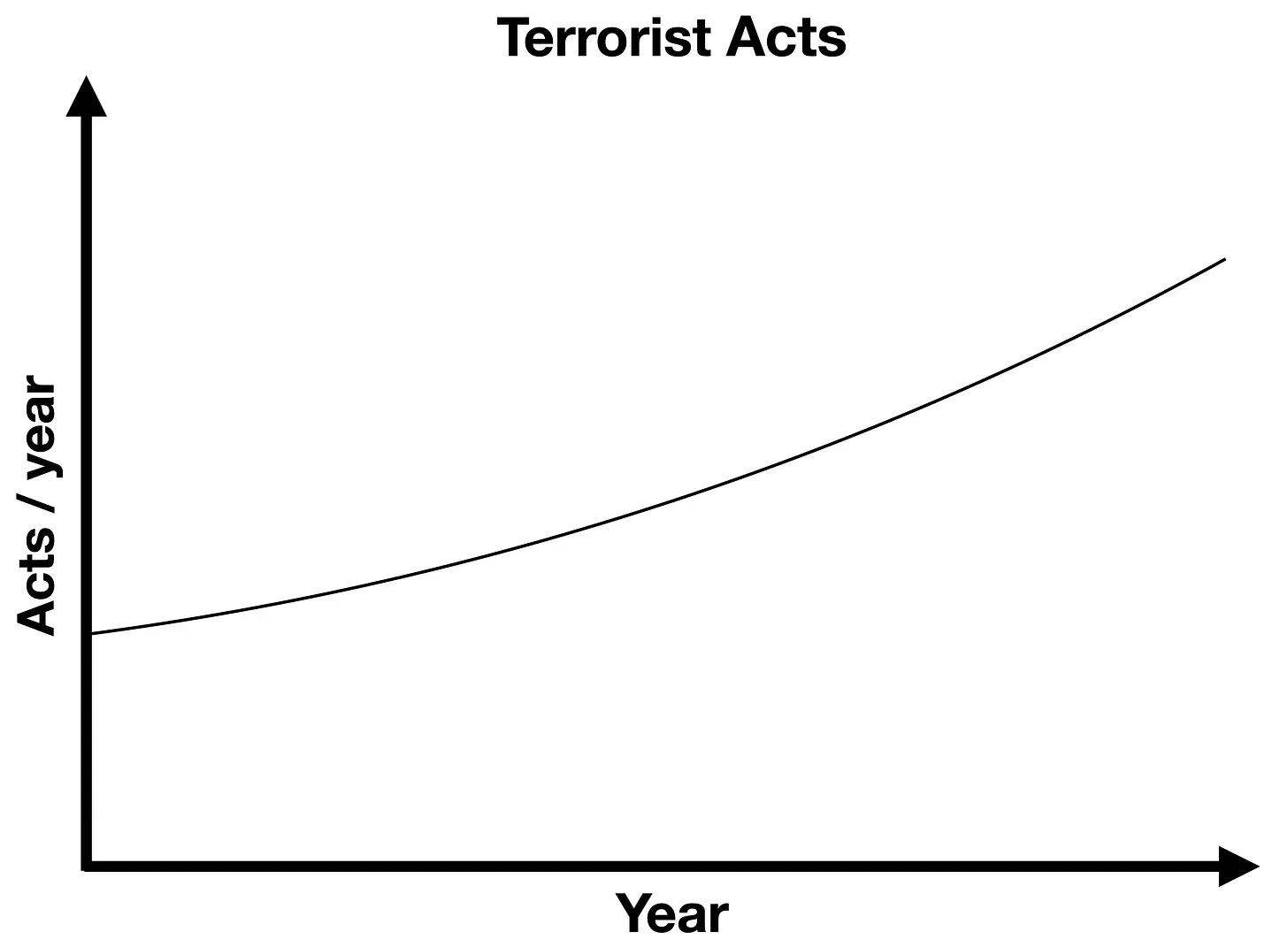

In the context of terrorism, it is common in the United States to focus on a single event like 9/11, while overlooking the long history of observable behaviors that could have predicted it. There had been escalating tensions, punctuated by events such as the bombing of the USS Cole and the subsequent US response, as well as actions by the US that supported those considered enemies of terrorist organizations. Adopting a broader, longer-term perspective enhances the quality of any mental model attempting to understand the expansion of terrorism—it helps us identify the causal structures driving it.

Organizations often focus on recent events, such as the last quarter’s profit margin, this week’s layoffs, or current scandals. For instance, the 2008 mortgage crisis in the US (and globally) is a notable example. Initially, in mid-2008, people believed it was a recent phenomenon, likely due to poor management decisions by a few. However, a longer-term perspective reveals that the US economy since the 2000 “sell-off” was stimulated by lower interest rates set by the Federal Reserve. Additionally, granting subprime loans increased at a much faster rate than disposable incomes could sustain. In response, the Federal Reserve resorted to lowering interest rates once again to address the crisis.

The power of an event is undeniable, but unfortunately, we often react impulsively to it. Layoffs, reassignments, extra bureaucratic oversight, and even military invasions are common knee-jerk responses. However, understanding the world and its causes requires the ability to identify patterns of behavior.

REDUCING YOUR STATE’S MEDICAL COSTS

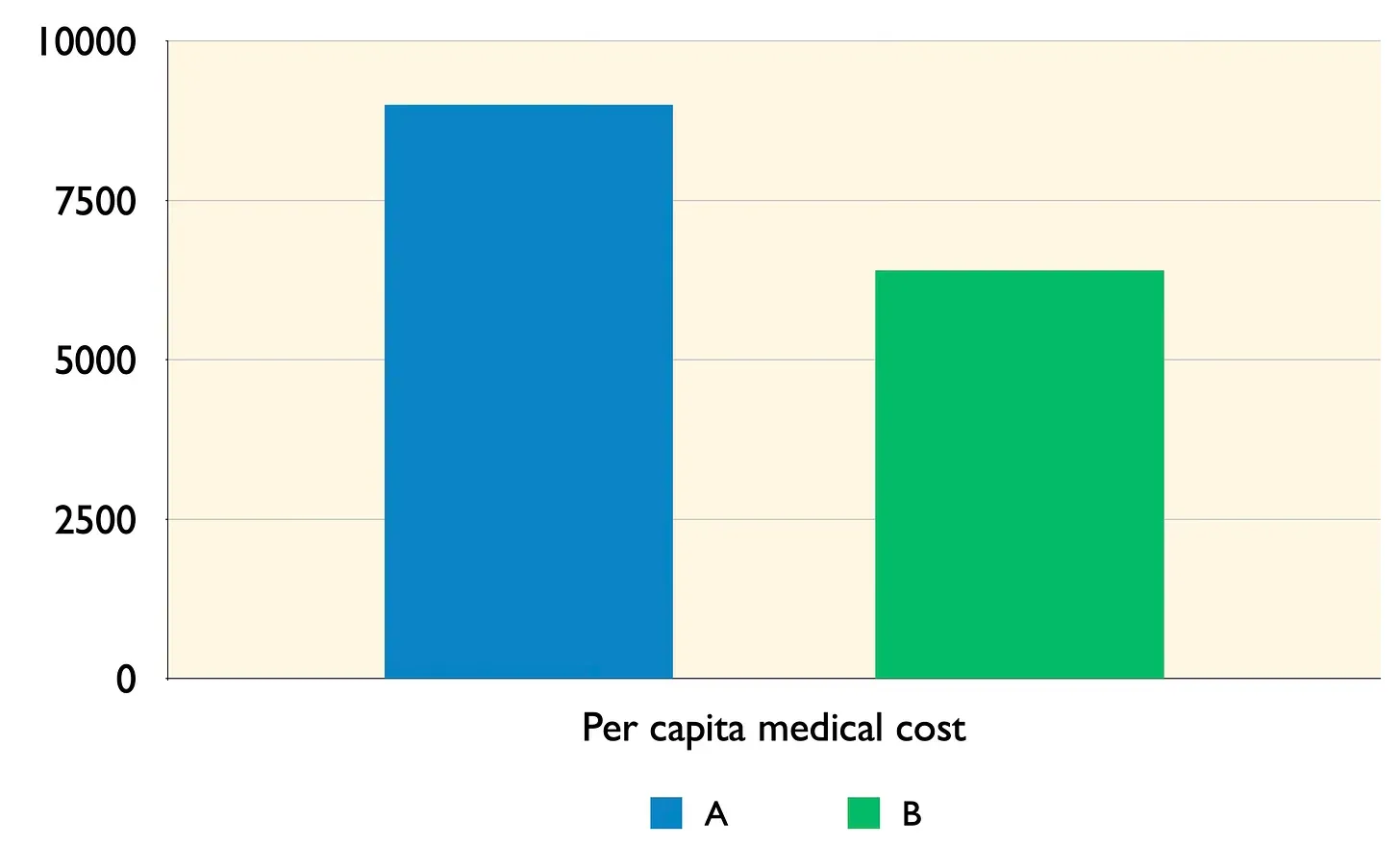

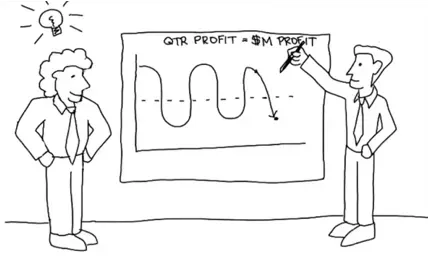

You’re working on your state’s initiative to reverse the rising medical costs. You’ve selected two states to benchmark, and based on their performance, you’ll contact your counterpart in each state to learn from their strategies.

Here are the per capita medical costs for two states. Which one, based solely on this data, would you choose as your benchmark for “best practices”?

he obvious answer is State B.

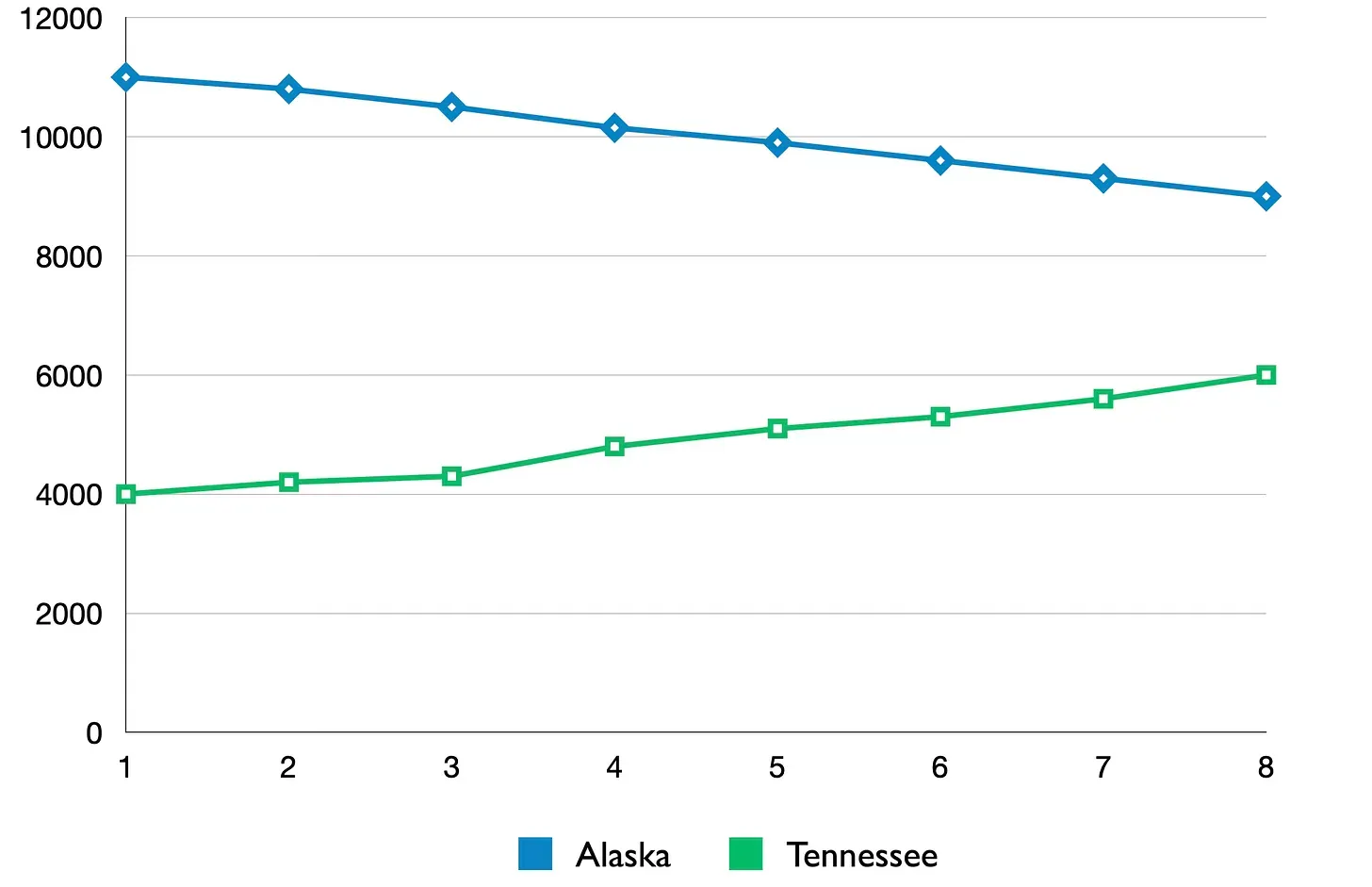

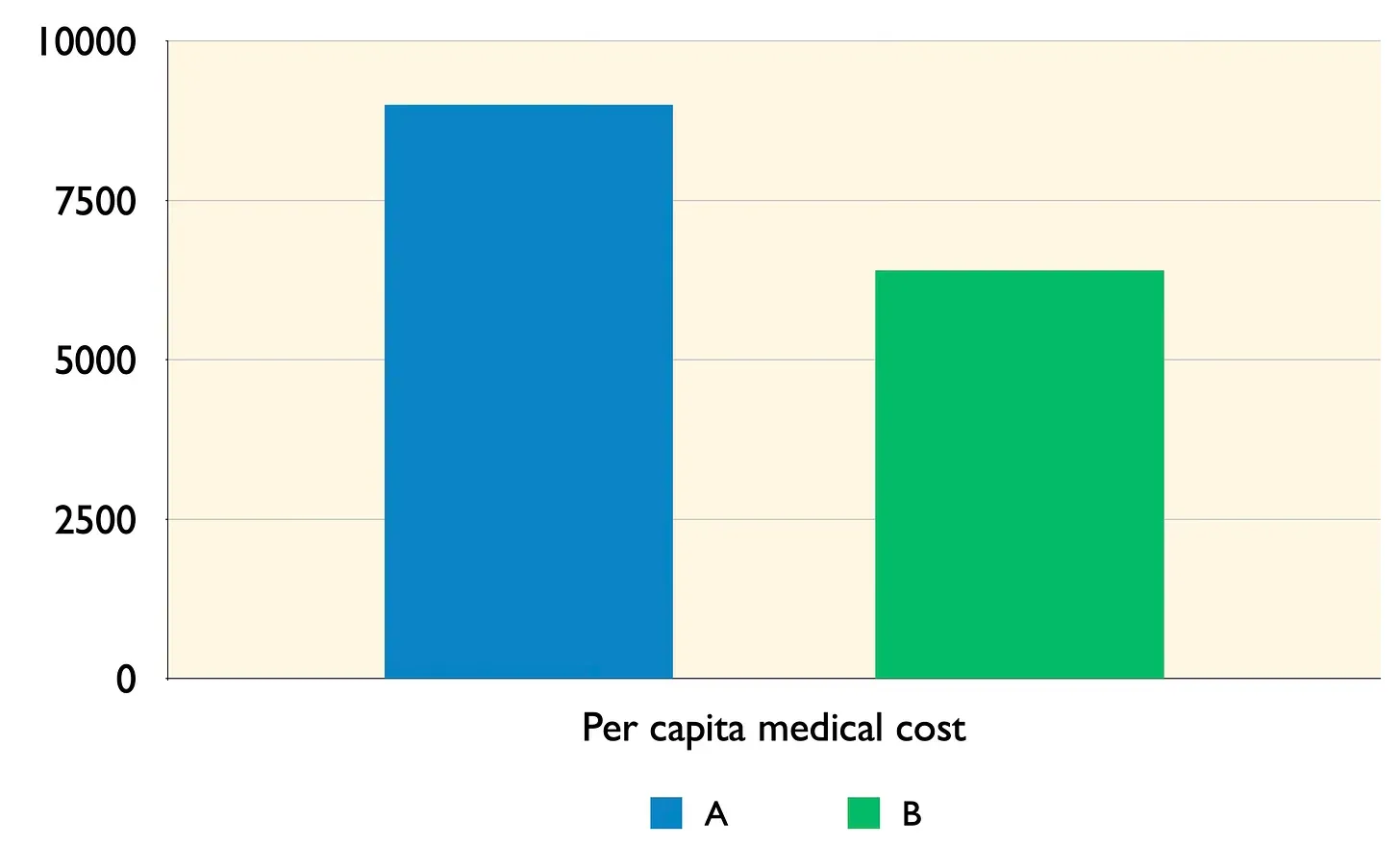

However, before you draft an email to your counterpart in State B, your assistant bursts into the room with this chart. Now, which state should you contact to learn from their successful practices?

This time the answer is State A.

This illustrates why it’s often beneficial to analyze metrics through the DYNAMIC Thinking lens. First, relying solely on “point in time” data can lead to incorrect conclusions. We frequently make decisions based on narrow time slices of data, which could be detrimental.

Second, comparisons between similar entities, such as states vs. states, cities vs. cities, or countries vs. countries, that only use single numbers can be misleading. Even if two states have the same per capita medical costs, if their trends are similar to those observed here, one may be experiencing rapid deterioration. They are not comparable at all.

Trend lines, on the other hand, often trigger deeper, more rigorous mental models. They provide an operational narrative that enhances our thinking, decisions, and strategies. In this case, observing the trends revealed a story about the direction of performance and clarified the clear winner.

So a good SysQ tenet is:

When something’s important, look at it as a trend over time.

TIME DELAYS: ANOTHER REASON WE NEED DYNAMIC THINKING

In many cases, decisions made today may not have a desired impact on the organization for years. For instance, the Beer Game, a popular learning tool, illustrates our inability to comprehend time delays. Thousands of executives, MBA students, engineers, and others who have played this game have struggled to manage their inventories, even when the retail demand is linear and predictable. Anyone who has played this game understands how inherent time delays in a system’s structure contribute to its performance.

This common limitation also affects our understanding of climate change. John Sterman and Linda Booth-Sweeney have shown that a majority of their subjects (MIT students) cannot predict how long it will take a decrease in carbon emissions rates to impact global climate temperatures, even when the assumptions are clearly stated.1

Ignoring time delays is a major contributor to the planning fallacy. This fallacy occurs when our predictions about the time required to complete a future task are overly optimistic, leading us to underestimate the actual time needed.

Overlooking time delays often results in the common “worse before better” dynamic when implementing public policies or organizational improvements. Public sector managers, rightly so given the public’s understanding of dynamics, avoid policies that may eventually improve situations in the long run but may worsen conditions in the short term.2

THE SHAPE OF A MOVIE

In 2017, we witnessed a plethora of extraordinary yet peculiar movies. Among them, The Shape of Water emerged as the most peculiar of all, potentially claiming the coveted Academy Award for Best Picture.

Its premise, centered around a mute woman named Elisa’s profound love for a creature that resembles a fish more than a human, may initially appear absurd or even laughable. However, this film achieved remarkable success, garnering numerous accolades and captivating audiences.

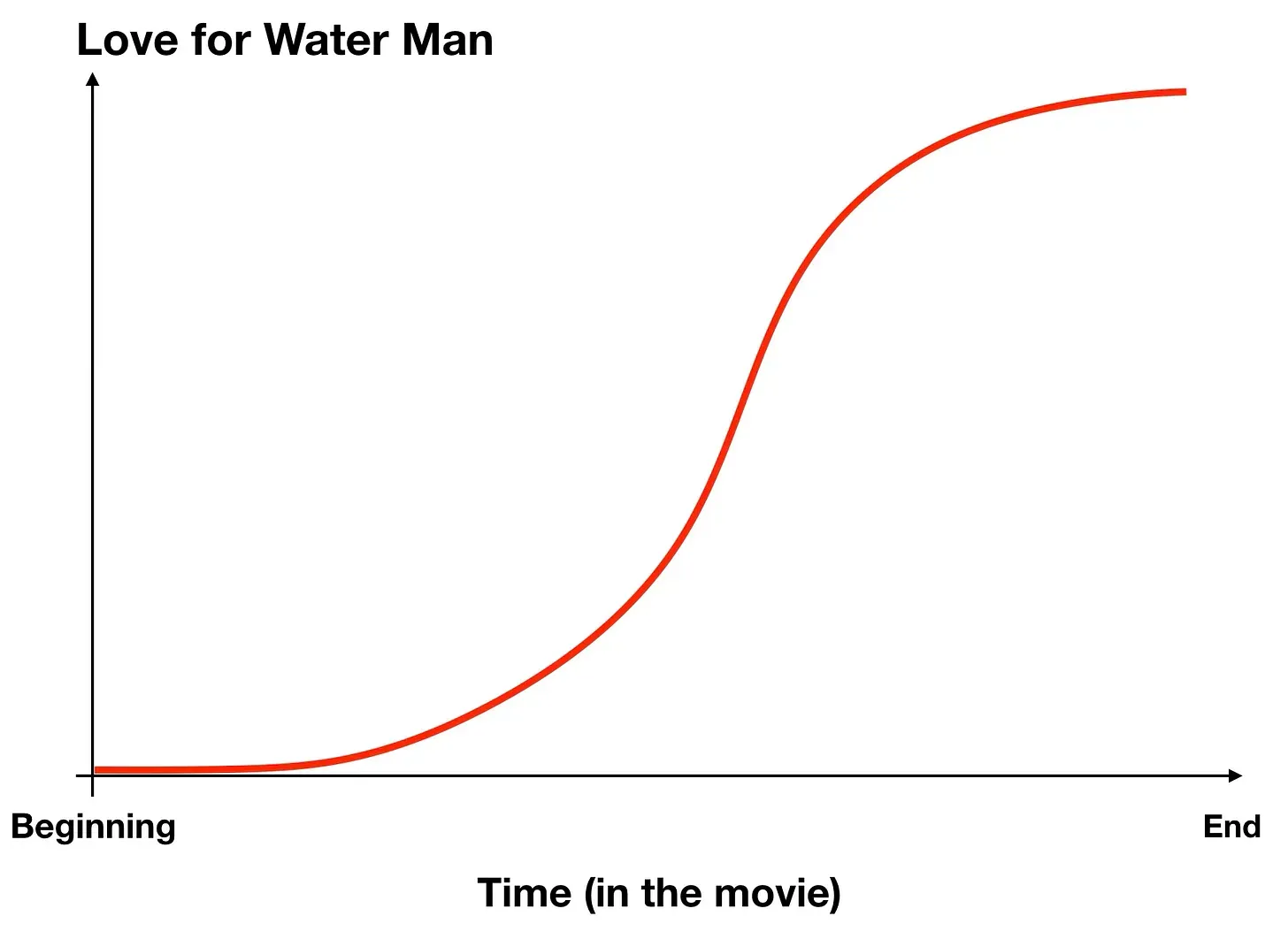

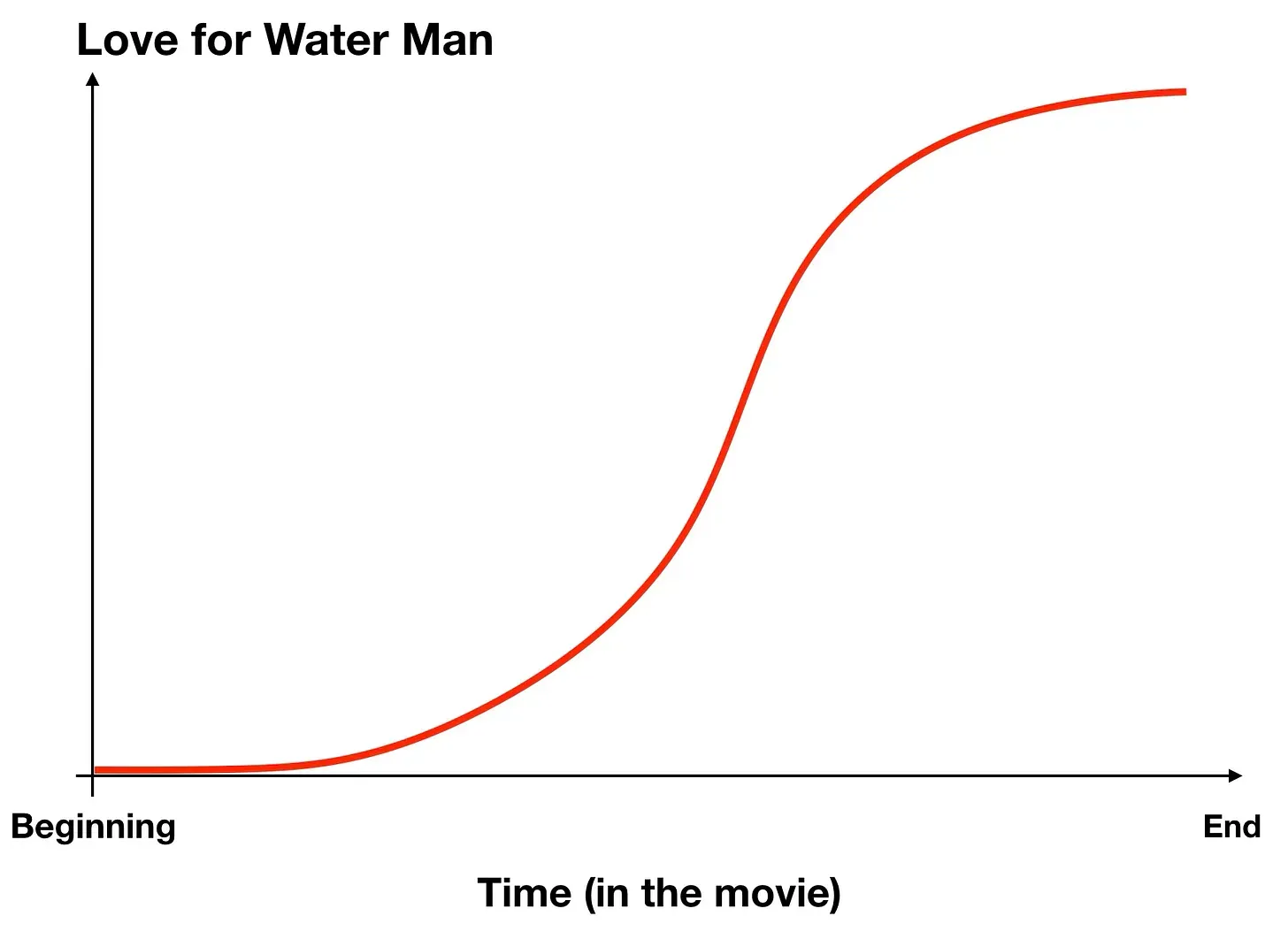

The trend line for her love of the water man is shown here.

The Shape of Water’s success lies in its ability to gradually reveal credible reasons for Elisa’s growing affection for the water-dwelling entity. This gradual progression allows viewers to comprehend and even predict her actions throughout the movie. If you were to watch only the last third of the film, you might find the scenes so absurd that they would be difficult to take seriously, potentially leading you to leave the theater.

However, by watching the entire movie from the beginning, you are presented with a rational, rigorous, and dynamic mental model that enables you to grasp and even anticipate the protagonist’s actions.

STARTING A SYSQ ANALYSIS? FIND THE PLOT FIRST!

At the outset of every SysQ initiative, establish a clear purpose. Collaborate with your team members and stakeholders who need to be involved. Ensure that everyone is aligned in understanding the purpose of the mapping, modeling, or SysQ analysis.

The purpose is to comprehend the underlying causal factors that contribute to ____________. This knowledge will enable us to develop more effective strategies, policies, or levers to influence ____________ in the future.

While verbal descriptions can suffice, visualizing trends over time through a trend graph can significantly enhance the impact and utility of the analysis, particularly in collaborative settings.

OPERATIONAL THINKING — FOCUSING ON THE PHYSICS — REQUIRES CLARITY ON THE TRENDS

OPERATIONAL Thinking — focusing on the physics — is fundamental to high SysQ and applying it involves gaining a comprehensive understanding of the systemic structure that generates the desired behavior. Clarity on the behavior is not merely a desirable outcome but a prerequisite for effective SysQ application.

The process of clarifying the trends, drawing and agreeing on these trends, aligns everyone on the same page regarding their underlying reasons for working together. It provides a clear vision, fostering strong motivation for collaboration. Therefore, I allocate significant time early in any consulting engagement to assist my clients in achieving vivid and rigorous clarity on the purpose: the trends they intend to influence.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS OF DRAWING TRENDS OF INTEREST

Gaining clarity on trends helps focus effort and develop a vision of success. But it offers many other benefits as well.

Benefit 1

It automatically shifts collaborators into a generative process. Seeing a trend line prompts the mind to seek understanding. Why does this happen? This prompts us to delve into our mental model database, searching for past experiences that might explain it. We transition from reactive thinking—“How do I react to this?”—to becoming more inquisitive and reflective. We seek causality and explore what generates the behavior or enter a generative process.4

Benefit 2

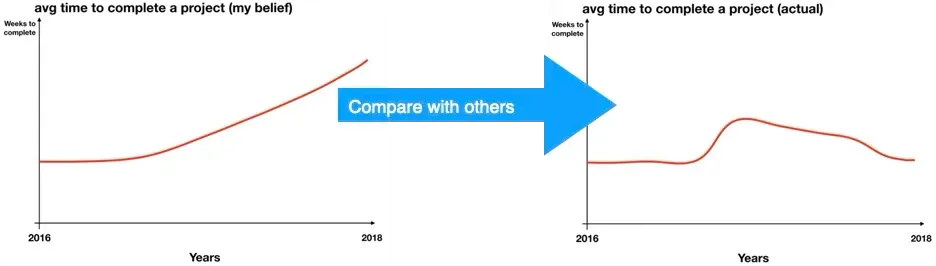

It helps identify faulty thinking by comparing our perceived trends to what others believe or know. Sometimes, our assumptions are incorrect.

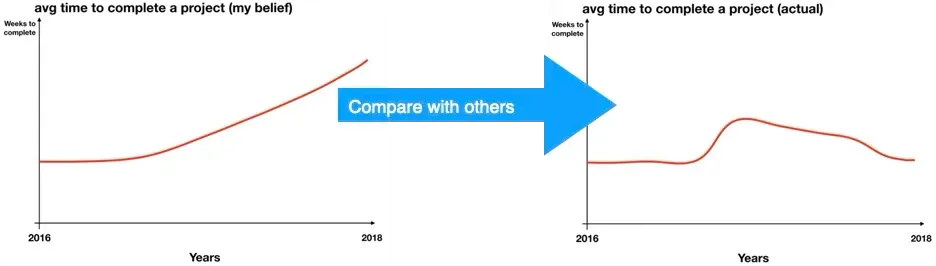

Let’s say I believe that our projects are taking increasingly longer to complete, perhaps because my last two actually did. I might suggest to colleagues we need to invest in some improvement, perhaps upgrade the IT system. Instead of promoting a solution to a nonexistent problem, if I drew a trend line similar to the one shown below, I could share with others, including those who have the data.

I’d then have the opportunity to learn why my assessment of reality was so far off. Yes, I’d have a learning moment. In this case I’d learn that I was still holding onto the increase in project time that happened late 2016 when several employees left. And even though project times had steadily improved since then, my confirmation bias kept me looking for the trend to go the other way. In this case, I learned something about myself.

I’ve seen the process of drawing trends help legislators who are normally disagreeable with one another become collaborative because they had some inaccurate understanding corrected. If seen engineers show trend lines to management to help them become more concerned about where a staffing issue was likely trending in the not too far future.

Benefit 3

Asking others you wish to be part of the effort to draw trends they are most concerned with–trends that may not be ones you initially used in trying to motivate their involvement–may help you find common ground. It may also help you expand your field of vision.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT USING TREND GRAPHS

Check out this substack’s resources section to learn about several trend graph types you’ll find useful across a diverse range of purposes and activities.

1

J. Sterman and L. Booth Sweeney, Understanding public complacency about climate change: adults’ mental models of climate change violate conservation of matter, Springer Netherlands, Vol. 80, Numbers 3-4

2

Soderquist, C. Facilitative Modeling: Using Small Models to Generate Big Insights, The Systems Thinker, Pegasus Communications, December, 2003

3

Forbes, 'The Shape Of Water' 4K Blu-ray Review: The Ultimate Wet Dream, Mar 19, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnarcher/2018/03/19/the-shape-of-water-4k-blu-ray-review-the-ultimate-wet-dream/

4

Calancie L, Anderson S, Branscomb J, Apostolico AA, Lich KH. Using Behavior Over Time Graphs to Spur Systems Thinking Among Public Health Practitioners. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:170254. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170254.

The authors used trend graphs with teams in maternal and child health. 86% of participants found the technique improved their thinking and engagement enough to indicate they would use these tools after the workshop.

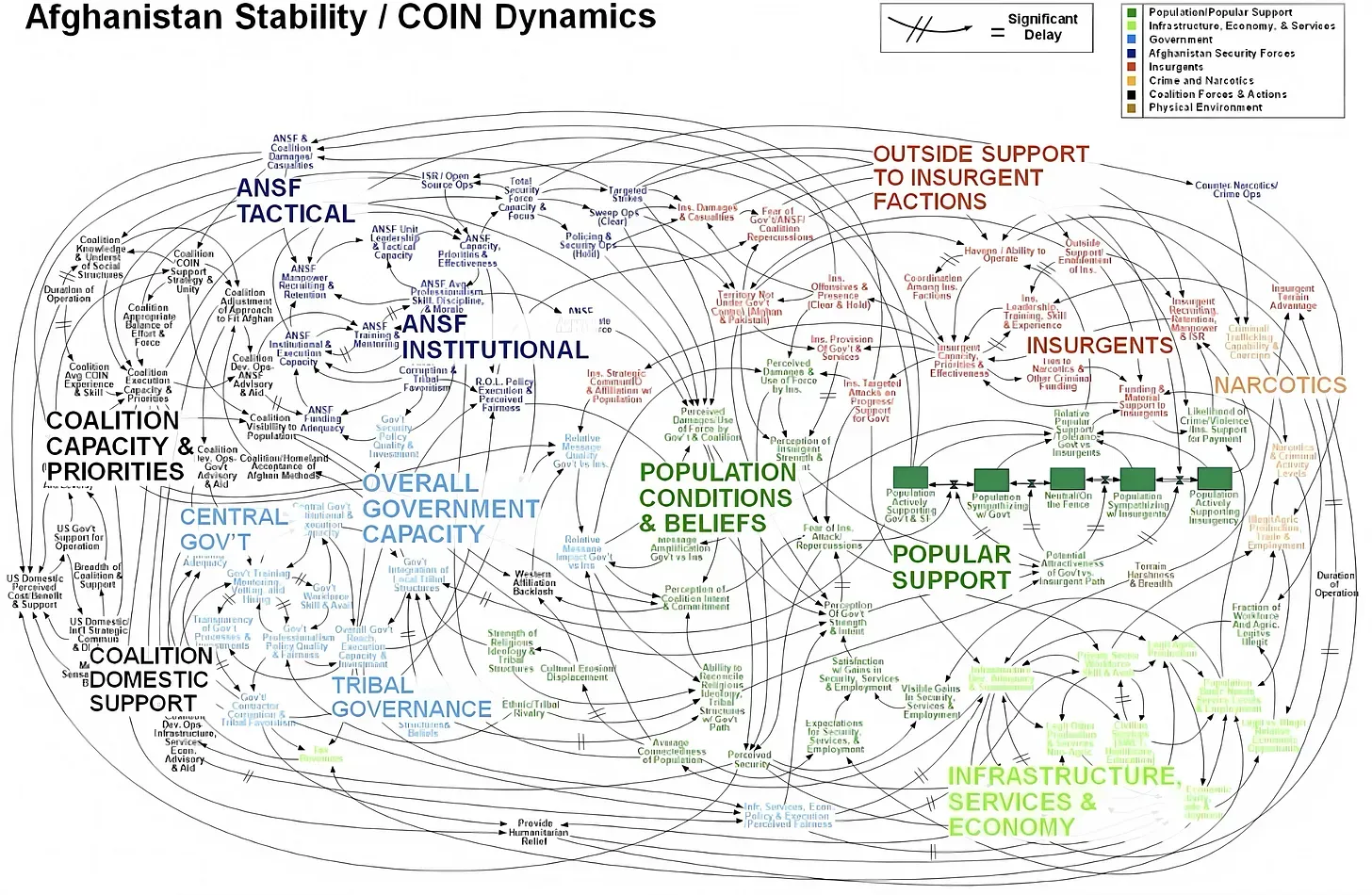

The High Road process involves sharing the initial “starter map” or “starter model” with others. Does it provide a clear explanation of why the performance issue is occurring? What changes or additions are needed? Make small adjustments and share the updated model for testing.

The High Road process involves sharing the initial “starter map” or “starter model” with others. Does it provide a clear explanation of why the performance issue is occurring? What changes or additions are needed? Make small adjustments and share the updated model for testing.

Bad, right? Worried?

Bad, right? Worried?

Now how do you feel?

Now how do you feel?

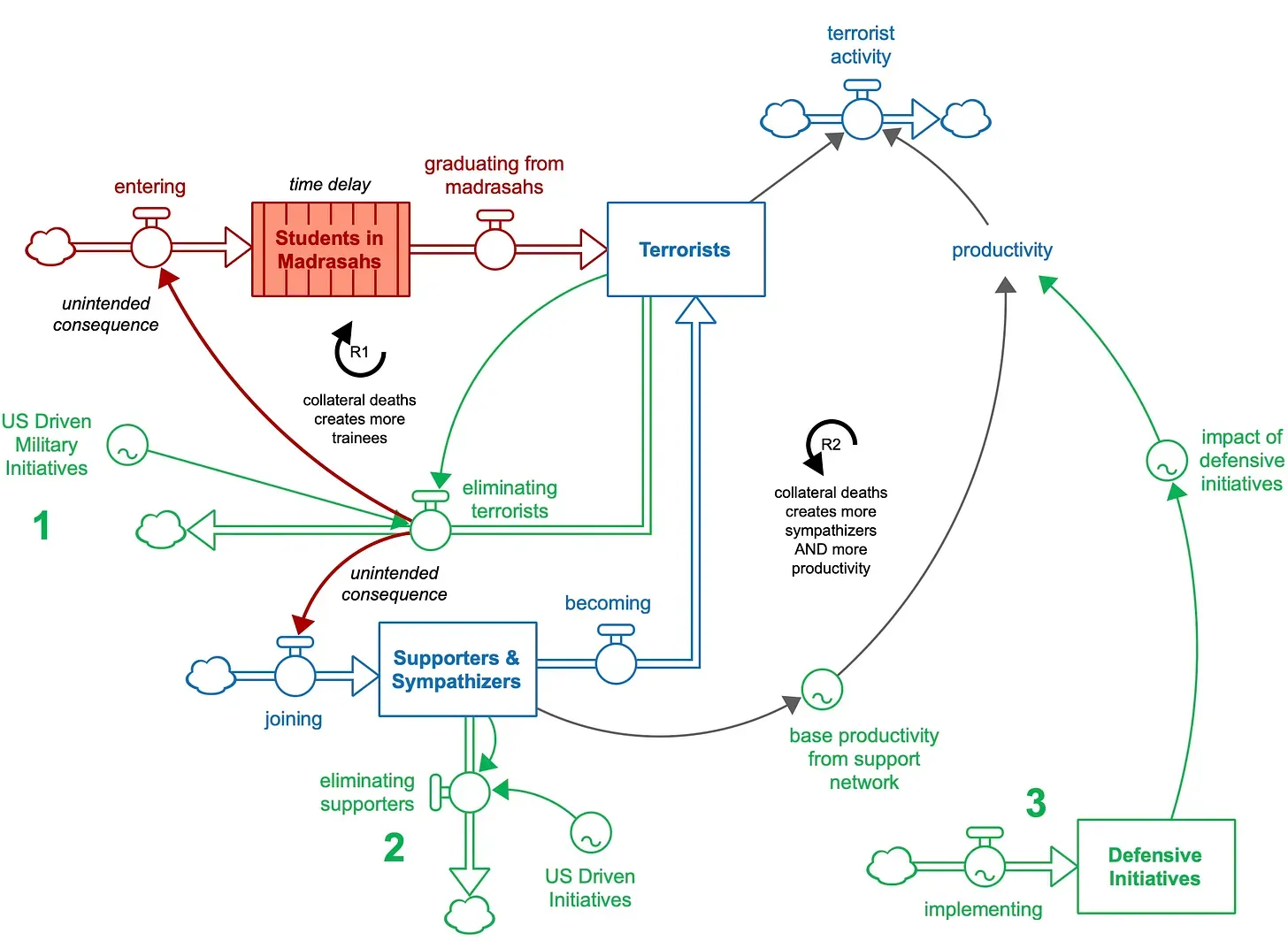

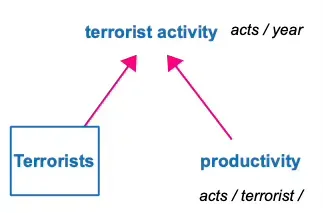

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.