TOOLS

Attribute of Tools

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua

About

Overview of the attribute. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

The SysQ AIM (Mindset) and SysQ APTITUDE (Thinking Skills) guide us in seeing the world and analyzing complex challenges, but it’s the Tools that make our thinking visible, shareable, and actionable. These tools aren’t just ideas; they’re practical instruments that help us map, understand, and improve the systems that shape our lives. From simple SysQ Questions that can be used in any meeting to sophisticated simulation models that predict system behavior, each tool has a specific purpose in turning complex challenges into manageable opportunities.

Think of these tools as different lenses through which we can examine reality — each one revealing different aspects of the same system. Just as a carpenter wouldn’t use only a hammer for every job, systemic intelligence practitioners need multiple tools to effectively understand and influence complex systems. The key is knowing which tool to use when and how to combine them for maximum impact. In the following sections, we’ll explore each tool in detail, showing you not just how to use them, but when and why they’re most effective.

IT’S EASY TO FOCUS ON THE TOOLS FIRST

During the 1990s, organizational learning became the leadership fad du jour, with “systems thinking” becoming one of the biggest buzzwords of the decade. Everyone wanted to be systems thinkers. The Fifth Discipline, The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, and The Systems Thinker1 accelerated a broad diffusion of systems thinking tools and techniques that were adopted by private sector organizations, NGOs, schools, and communities.

accelerated a broad diffusion of systems thinking tools and techniques that were adopted by private sector organizations, NGOs, schools, and communities.

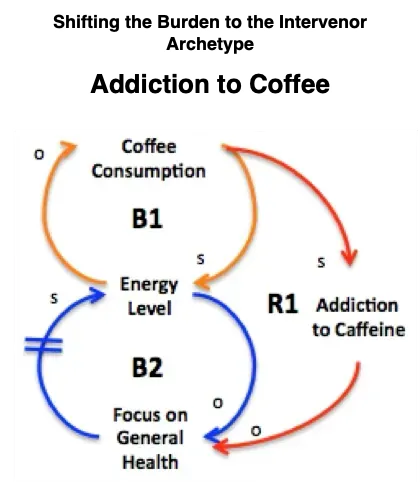

Systems archetypes were the most popular tools. These are recurring behavior patterns found in various systems. For instance, one archetype is called Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor.

This is when a company relies too heavily on external consultants to solve problems they could solve themselves. It’s also when someone becomes overly dependent on coffee to boost energy instead of getting enough sleep, eating well, and exercising; with changes to a few words it also applies to using alcohol to address anxiety. Archetype here from The Waters Center for Systems Thinking

Archetype here from The Waters Center for Systems Thinking

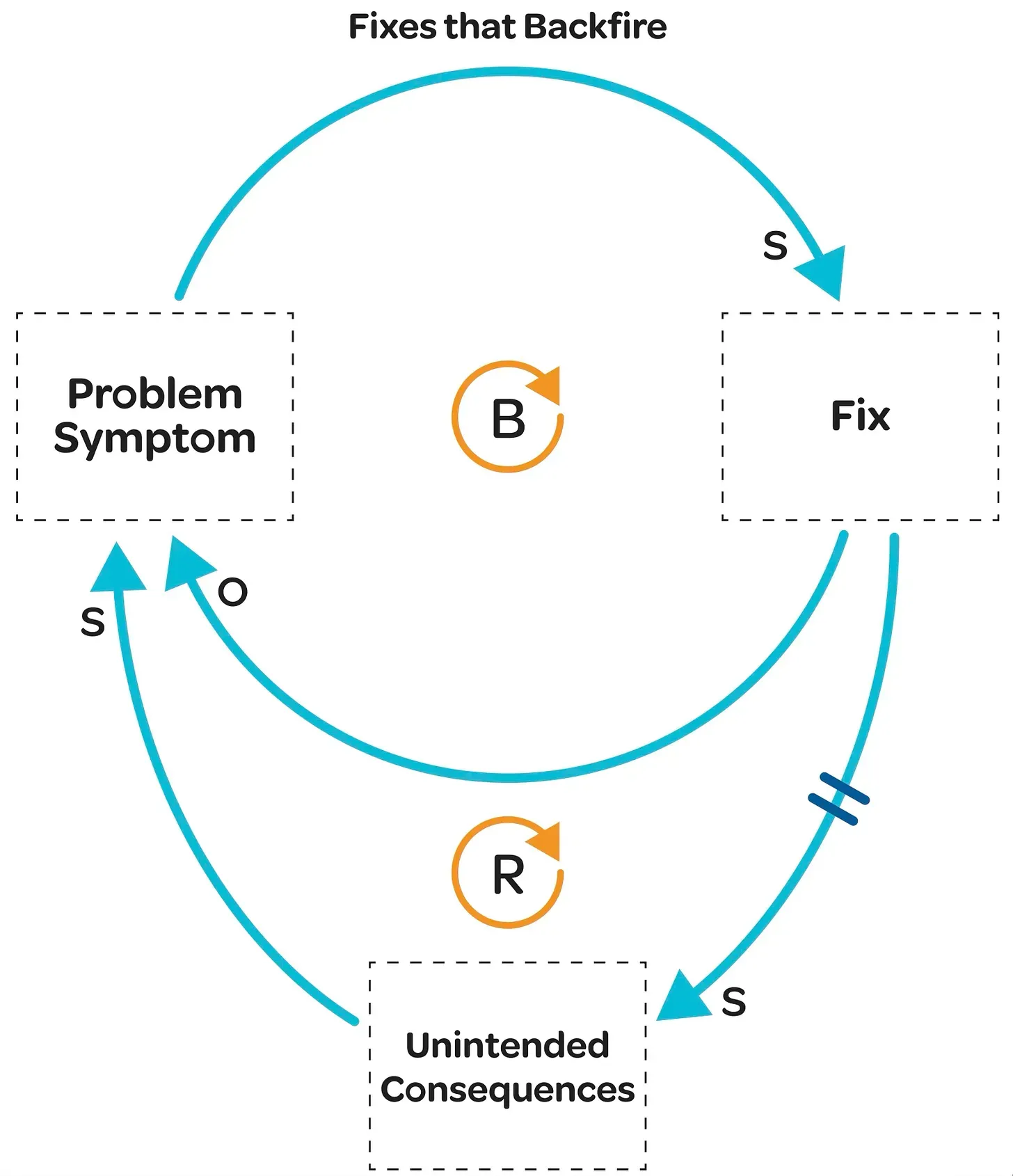

After studying many different systems, from businesses to ecosystems (even families), experts in the field identified a few common behaviors. Eventually, the systems thinking field settled on nine archetypes (like Fixes that Backfire,Shifting the Burden to the Intervenor, and Success to the Successful).

Fixes That Backfire, sometimes referred to as Fixes That Fail, is shown above. Besides using this substack, you can learn more about Fixes That Fail and the other archetypes from the Waters Center for Systems Thinking.2

These archetypes were helpful and easy to understand, so many people who wanted to use systems thinking got excited about them and only used these tools.

But there are many other tools and techniques that should be part of the SysQ toolbox. Some are easier to learn and apply than the archetypes. Others take years to master, but the insights and learning they offer are worth it.

ARTIFACTS (APPLICATIONS and TOOLS)

There are myriad tools — of varying complexity — you should put in your SysQ Toolkit. They include:

SysQ Questions

a set of carefully crafted inquiries that can be used in any conversation to quickly surface systemic patterns and relationships, making them perfect for meetings and initial problem exploration

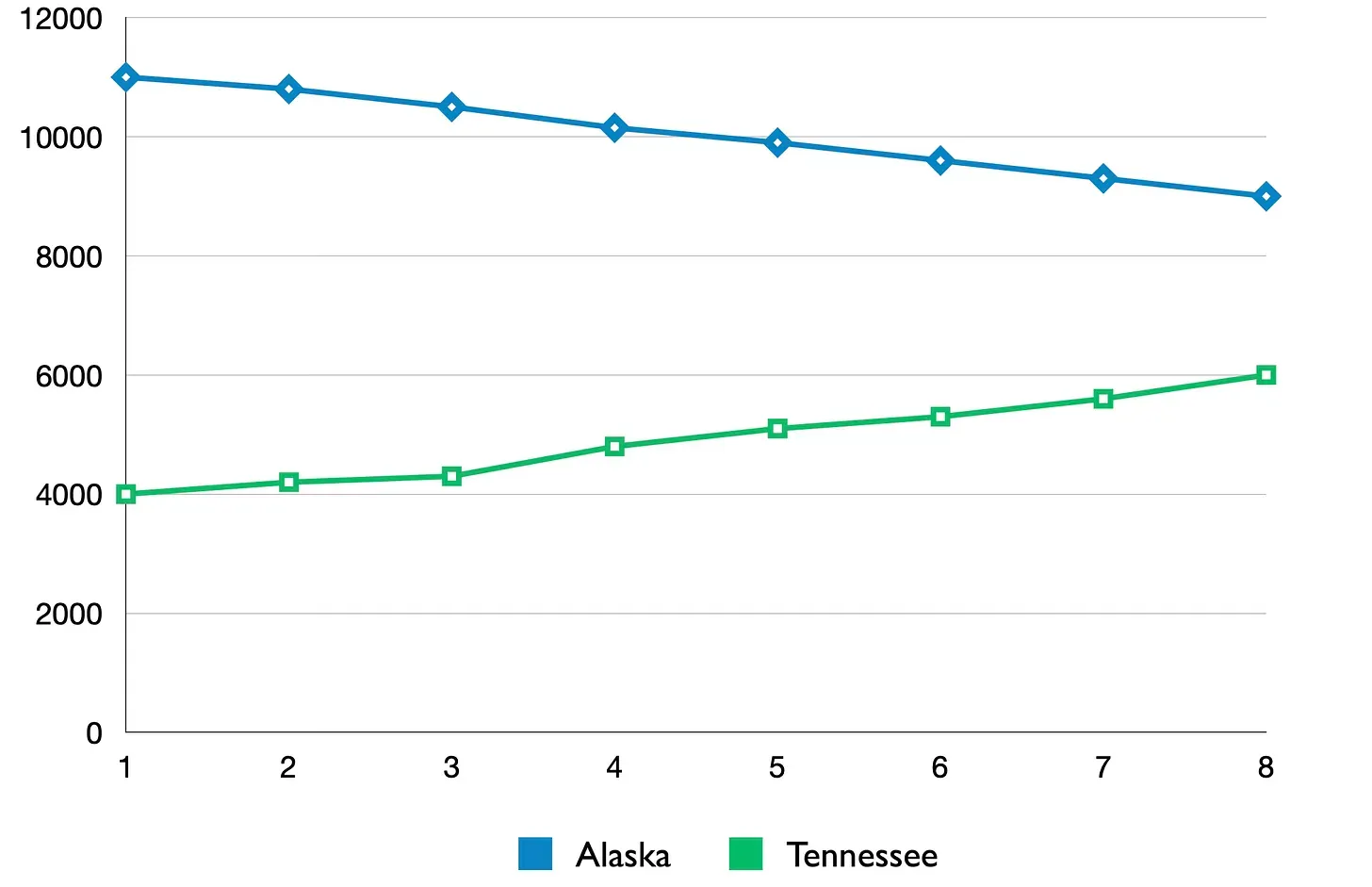

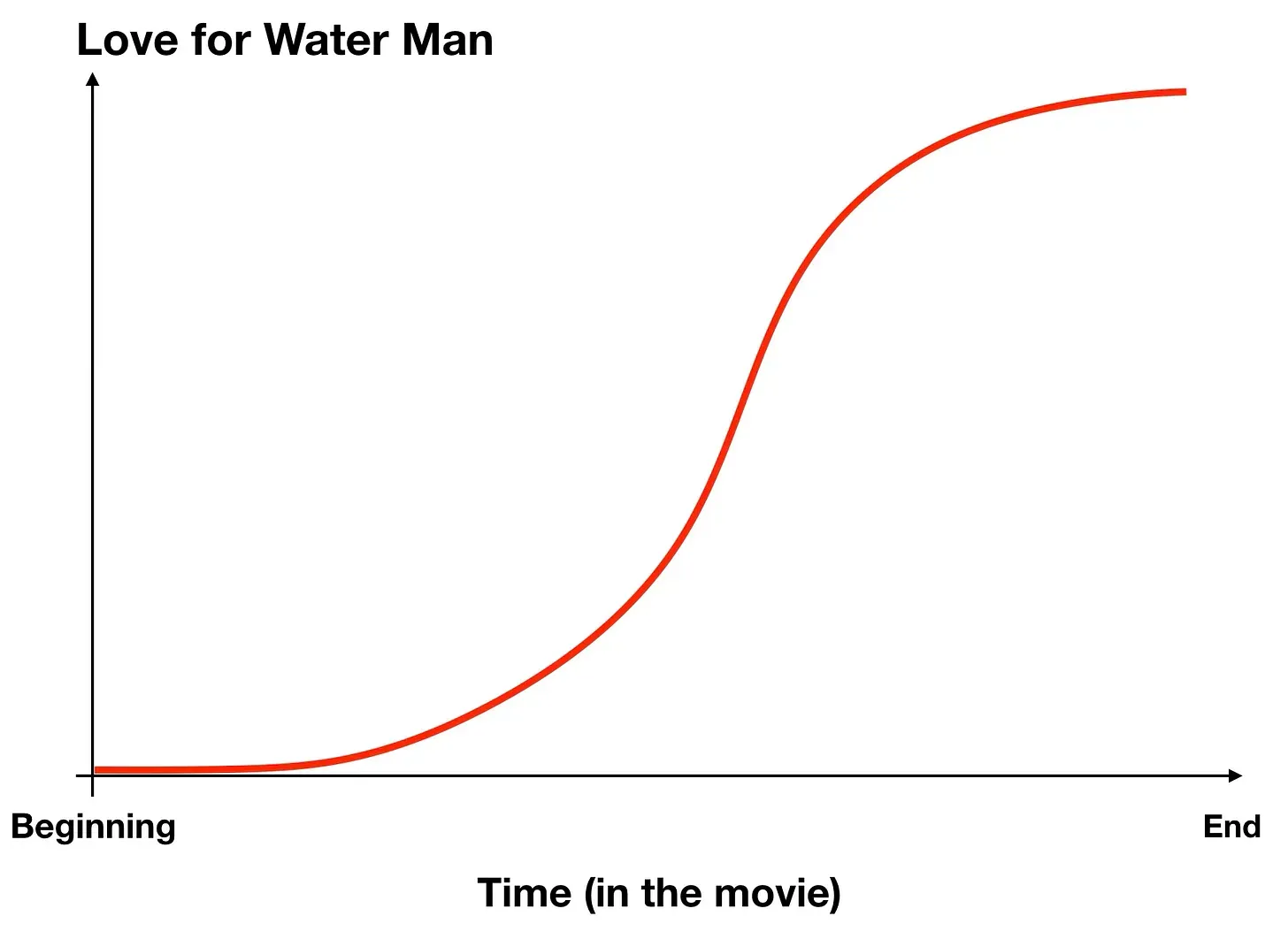

Behavior Over Time Graphs

help visualize how key variables change through time, revealing patterns and trends that might otherwise remain hidden in the complexity of data and stories

Multi-solving Tools

tools like FLOWER,3 guide us in finding solutions that address multiple challenges simultaneously, maximizing the impact of our interventions while minimizing unintended consequences

Systems Archetypes

recurring patterns of behavior found across different contexts and industries, serving as diagnostic tools to identify common systemic structures that often lead to problematic outcomes

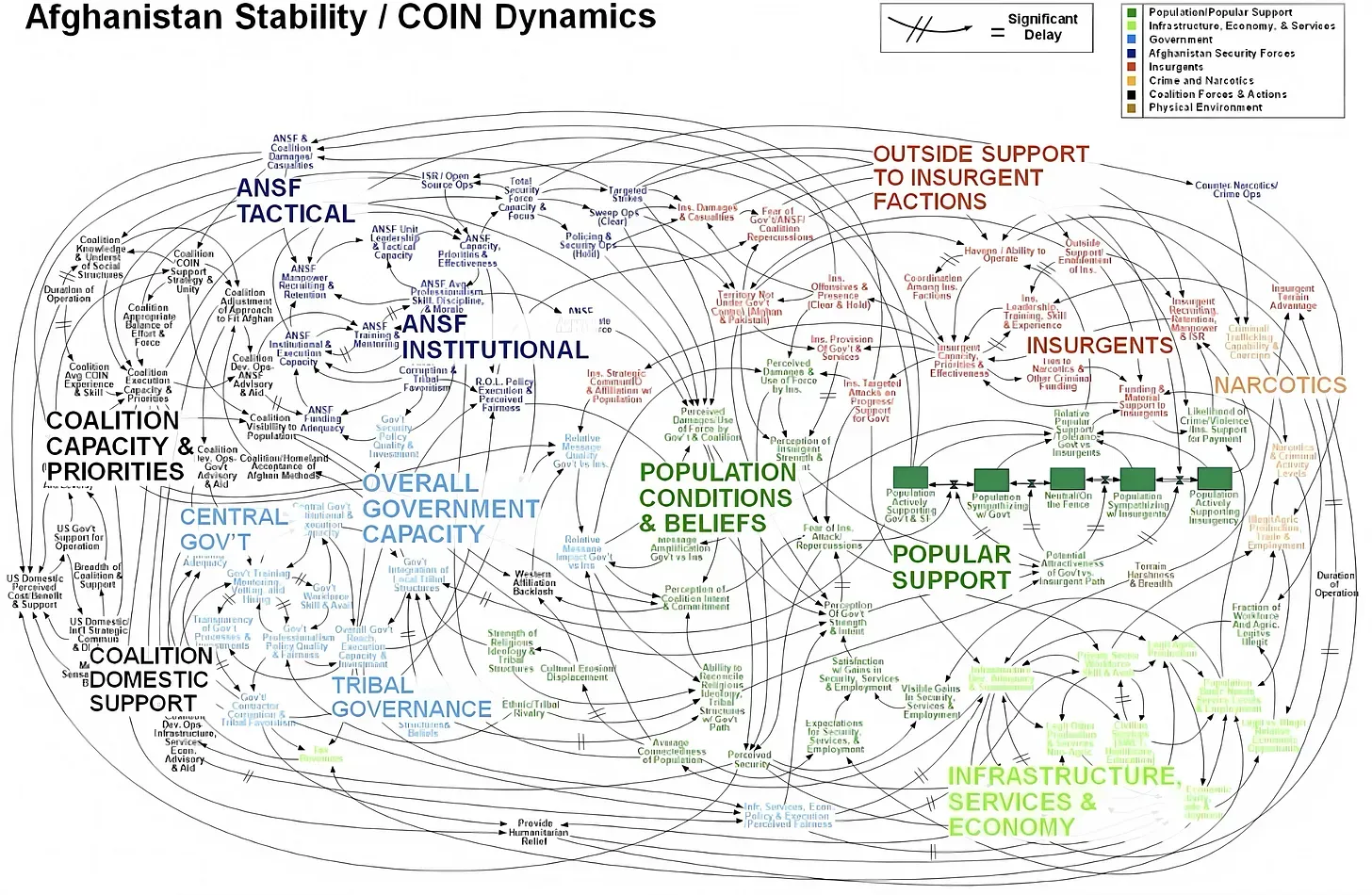

Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs)

map the circular nature of cause and effect in systems, helping us visualize how different variables influence each other and create feedback loops that drive system behavior

Stock and Flow Main Chains

identify the core structure of systems by tracking the accumulation (stocks) and movement (flows) of resources, information, or other variables that are central to the system's behavior

Stock, Flow and Feedback Maps

combine the power of stocks, flows, and feedback loops to create comprehensive visual representations of complex systems, revealing both structure and behavior

System Dynamics Models

computer simulations that bring these maps to life, allowing us to test different scenarios and policies before implementing them in the real world, providing the highest level of confidence in our understanding of system behavior

OPTIMAL TOOL? USES MINIMUM EFFORT / RESOURCES TO ACHIEVE REQUIRED CONFIDENCE

Each of these tools is like a special tool in our toolbox for understanding and changing complex systems. Some are easy to learn and use right away, while others take a bit more time and effort, but they give us deeper insights. The key is to know which tool to use when and how to mix them together to solve the problems we’re facing.

Many of these SysQ tools have been around for a while, and my colleagues and I have come up with some new ones to make it easier to use SysQ. For example, the SysQ Questions were created when I was teaching public health practitioners how to quickly improve the level of systemic rigor in conversations without having to use some of the more time-consuming visual tools.

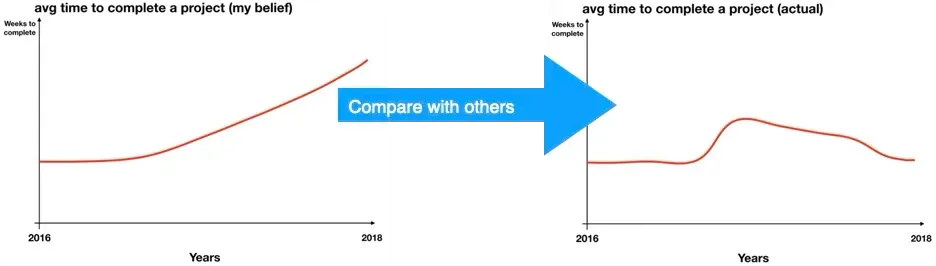

There are at least two ways to figure out if these tools are worth using. One way is to think about what you want to achieve with them. The main goal of all these tools and techniques is to make your mental model (the way you understand the world) better, more accurate, and more reliable. In other words, the tool should make you feel more confident that you understand the underlying forces (the basic things that make things happen) that are causing the performance you want to change or improve.

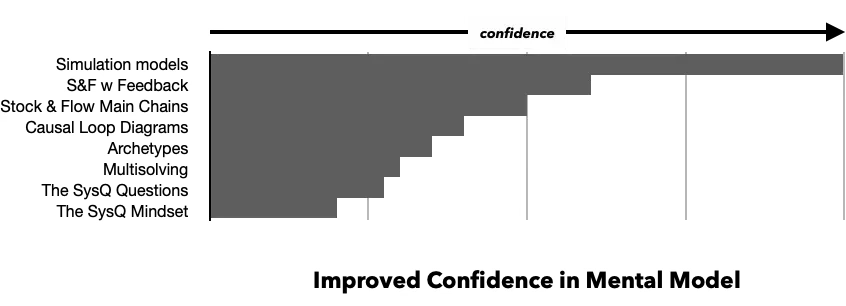

Building simulation models, if done well, creates the most confidence — because they must be internally consistent and use quantifiable data. Creating stock and flow maps can also give you a lot of confidence because they’re the foundation of simulation models and could be simulated if you added data to them. But since we can’t always predict how things will change without a computer, we don’t have as much confidence in our ideas as if we had a simulation model. The chart below isn’t based on any research or has any exact numbers.

Another thing to consider is how much time it takes to learn and use each tool. SysQ says that tools that are easy to learn usually take less time to apply and use. For example, people can learn the SysQ Questions in a few hours and immediately apply them in meetings. But the skills of a good simulation modeler take months or even years to learn, and it can take several months working with an organization to develop a simulation model that gives you confidence in your insights.

Another thing to consider is how much time it takes to learn and use each tool. SysQ says that tools that are easy to learn usually take less time to apply and use. For example, people can learn the SysQ Questions in a few hours and immediately apply them in meetings. But the skills of a good simulation modeler take months or even years to learn, and it can take several months working with an organization to develop a simulation model that gives you confidence in your insights.

Skilled SysQ practitioners are like tool experts who introduce and teach specific tools at the perfect moment. They help clients apply the tools in the right order based on their learning goals and what they want to achieve.

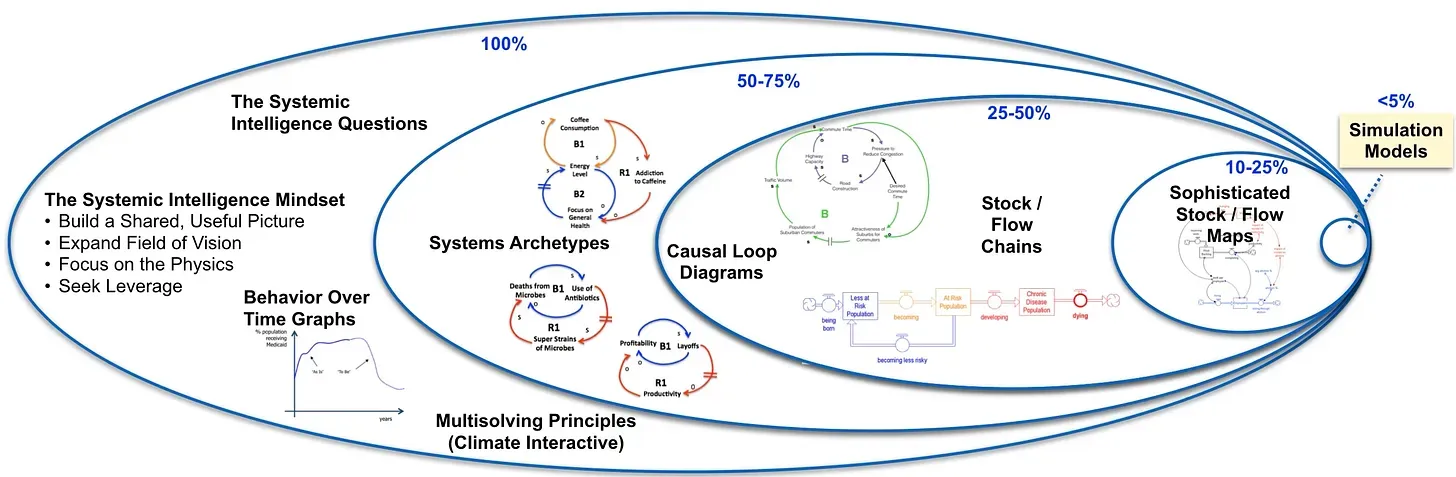

A VISION FOR CAPACITY BUILDING

Barry Richmond vision was everyone could learn systems thinking — at some level. It’s an innate intelligence that can be increased.4 Barry, when teaching system dynamics modeling to various multinational organizations, would show a Venn diagram (below) that suggests everyone should be able to read system maps, many should be able to draw simple maps, and a few should be able to build good simulation models. I’ve updated his original diagram to include additional tools used by other practitioners. Based on my experience teaching many of the SysQ tools above, I believe an ideal distribution of competency would see everyone using the mindset and SysQ Questions. Most would be able to read and apply archetypes, a few would be able to draw useful system maps, and a small percent would be able to develop simulation models. Such a distribution would create an ecosystem of creators, curators, and consumers of SysQ artifacts and insights.

Based on my experience teaching many of the SysQ tools above, I believe an ideal distribution of competency would see everyone using the mindset and SysQ Questions. Most would be able to read and apply archetypes, a few would be able to draw useful system maps, and a small percent would be able to develop simulation models. Such a distribution would create an ecosystem of creators, curators, and consumers of SysQ artifacts and insights.

The time it takes to learn and apply the tools and techniques increases exponentially the further right in the diagram. It takes a lot more time and skill to develop a map than to draw a behavior over time graph. And it takes exponentially more to develop a simulation model with dynamic questions and data. However, the amount of confidence in the insight generated from using tools on the right goes up. The type of insight and amount of time available are major factors in deciding which tool(s) would be most appropriate for your work.

“The framework, tools, and language of system dynamics should be accessible to all. Anyone can do this at some level, and everyone should try!”

–Barry Richmond

A WORD OF CAUTION ABOUT TOOLS: SOMETIMES WE CLING TO THEM AT OUR PERIL

We tend to cling to our tools — even when they’re not the best fit for the situation. Remember the saying, ‘a hammer looks like a nail’? Firefighters risk their lives by not putting down their tools when they need to run away from a wildfire.

“In Montana’s 1949 Mann Gulch fire, made famous in Norman Maclean’s Young Men and Fire, smokejumpers parachuted in expecting to face a “ten o’clock fire,” meaning they would have it contained by 10 a.m. the next morning. Until the fire jumped across the gulch from one forested hill slope to the steep slope where the firefighters were, and chased them uphill through dry grass at eleven feet per second. Crew foreman Wagner Dodge yelled at the men to drop their tools. Two did so immediately and sprinted over the ridge to safety. Others ran with their tools and were caught by the flames. One firefighter stopped fleeing and sat down, exhausted, never having removed his heavy pack. Thirteen firefighters died. The Mann Gulch tragedy led to reforms in safety training, but wildland firefighters continued to lose races with fires when they did not drop their tools.”5

Although the failure to set aside our favorite tools may not often have as deadly a consequence as firefighters who fail to do so, we can still be led astray. One common practice is to only apply systems archetypes to an organization’s problems. Newly minted “systems thinkers” may acquire a laminated chart of all the archetypes and scan it to understand all problems. Often an archetype doesn’t apply, so any insight from the chart is most likely unfounded — sometimes it could lead to a bad strategy.

In the case of the Challenger disaster, the standard tool was a having a “solid quantitative case” that the o-rings would be unable to withstand the unusually cold Florida temperatures. The Thiokol engineers who cautioned against giving the mission the green light couldn’t provide the rigorous analysis the managers at NASA required — their standard for the go/no go decision.

“NASA’s Mulloy [one of their senior managers] later argued that he “would’ve felt naked” taking Thiokol’s argument up the chain of command. Without a solid quantitative case, “I couldn’t have defended it.”

The very tool that had helped make NASA so consistently successful, what Diane Vaughan called “the original technical culture” in the agency’s DNA, suddenly worked perversely in a situation where the familiar brand of data did not exist. Reason without numbers was not accepted. In the face of an unfamiliar challenge, NASA managers failed to drop their familiar tools.”6

SUBSTACK MISSION: TEACH WHEN AND HOW TO USE EACH TOOL

Systemic intelligence is all about having the right tools at the right time to understand and influence our complex world. Imagine a master craftsperson’s toolkit, each SysQ tool has a specific purpose. From the quick-to-learn SysQ Questions that can transform any conversation, to the more sophisticated simulation models that can predict system behavior with amazing accuracy. The cool part is that this toolkit is scalable, so everyone can learn to use basic tools to improve their understanding, while those who invest more time can develop deeper capabilities to tackle more complex challenges.

What makes these tools truly powerful is how they work together to build our systemic intelligence. Whether you’re trying to improve organizational performance, address environmental challenges, or solve community issues, these tools provide a structured way to see beyond surface-level symptoms to understand and influence the underlying patterns and relationships that drive system behavior. By mastering these tools, you’ll develop the essential capacity needed to navigate and succeed in today’s interconnected world.

By exploring this substack, you’ll be able to answer:

Why should you use each tool and under what circumstances?

How does that tool work? When applied by an individual? When applied by a team or an organization?

How do you build and deepen proficiency to use each tool?

How do you teach the tools others?

How do you use to facilitate team learning?

“Man must shape his tools lest they shape him.”

—Arthur Miller

Additional Resources

Books

Book title as link | Description

Articles

Article title as link | Description

Online Resources

Resource title as link | Description

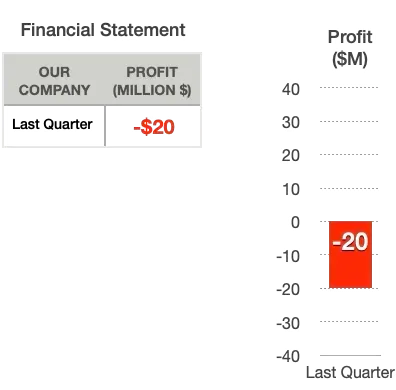

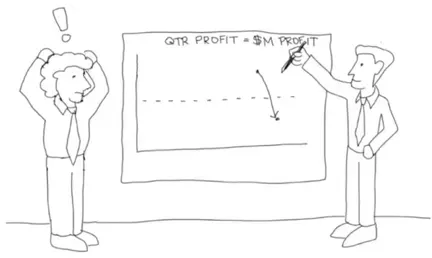

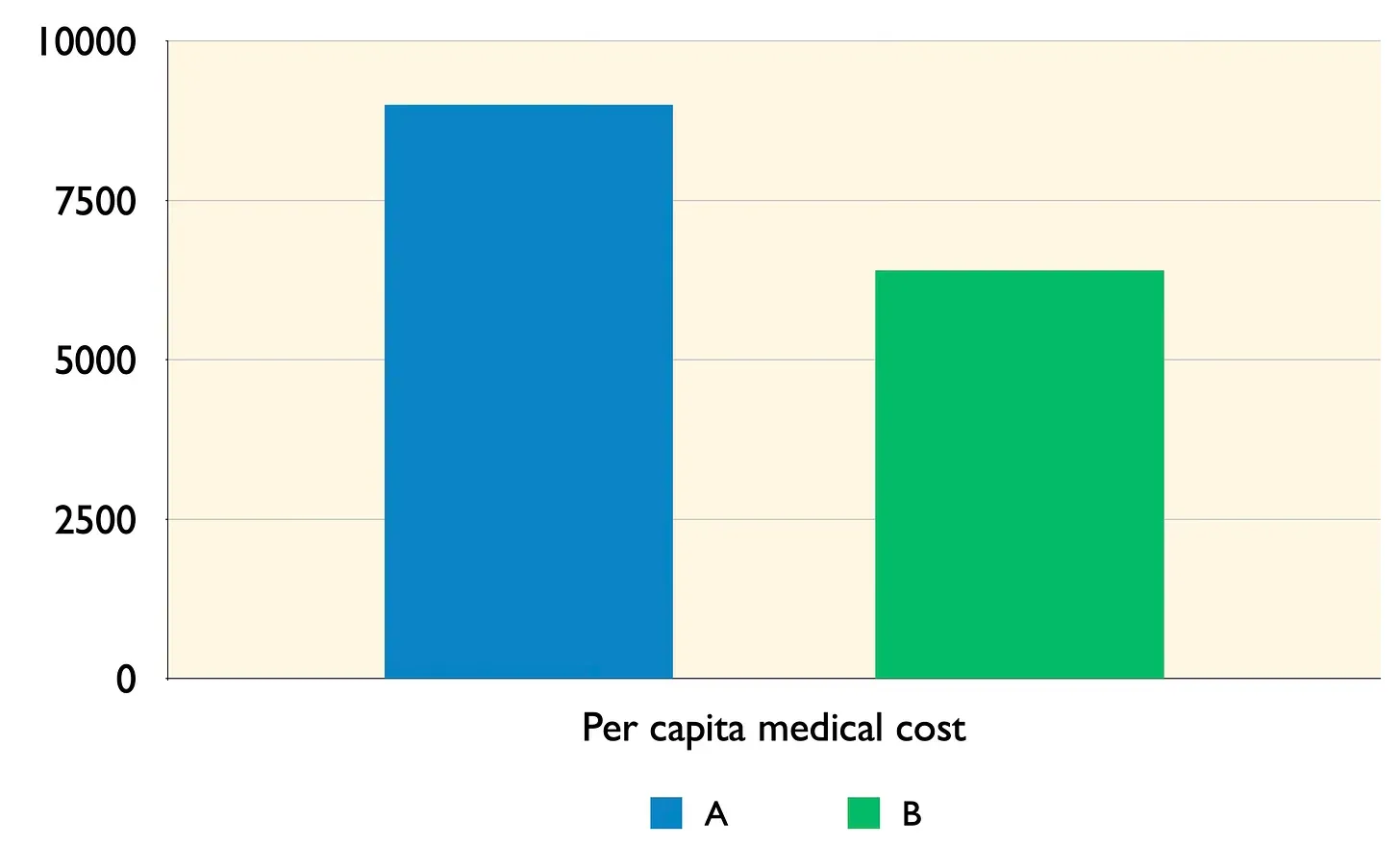

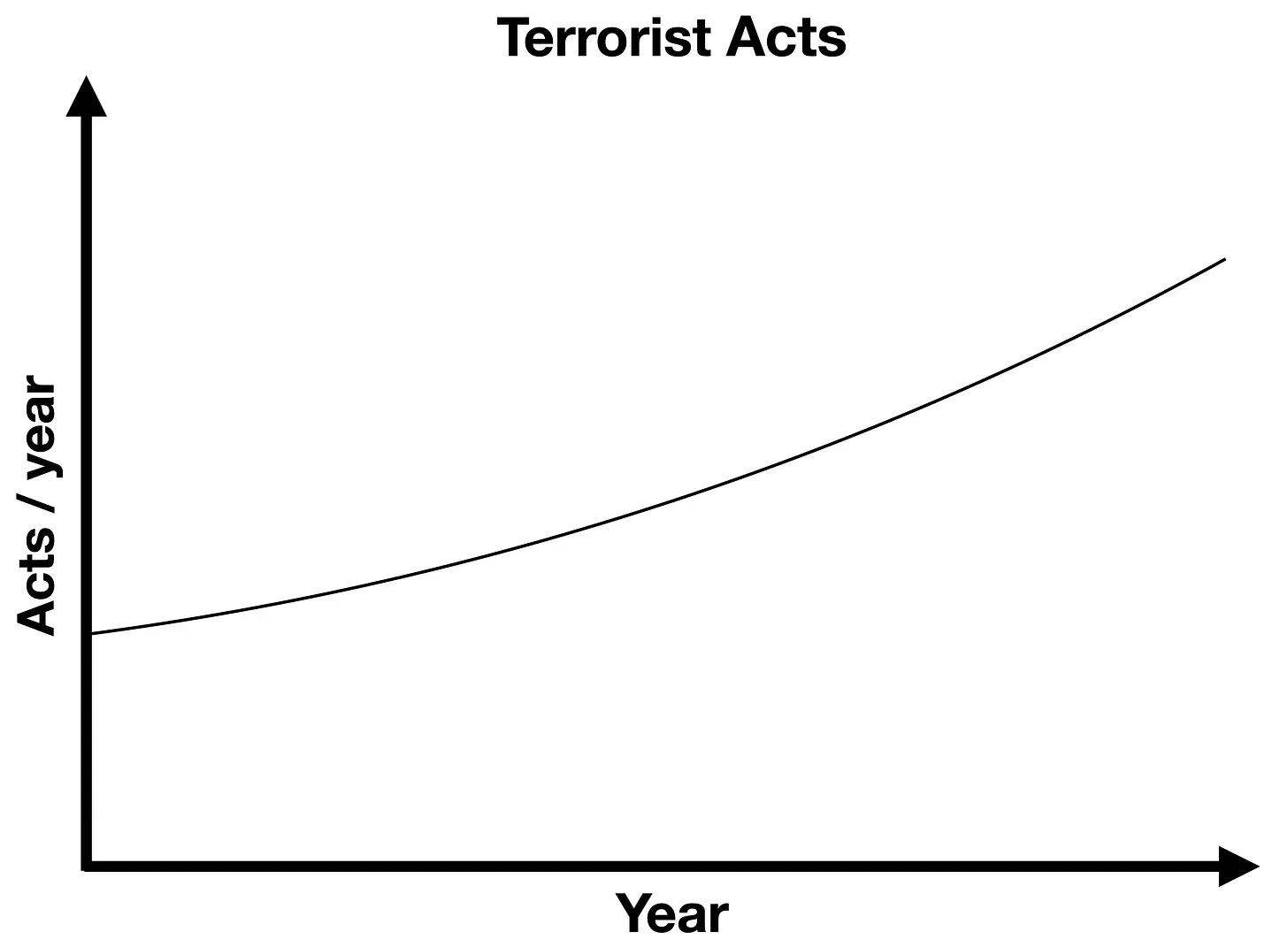

Bad, right? Worried?

Bad, right? Worried?

Now how do you feel?

Now how do you feel?

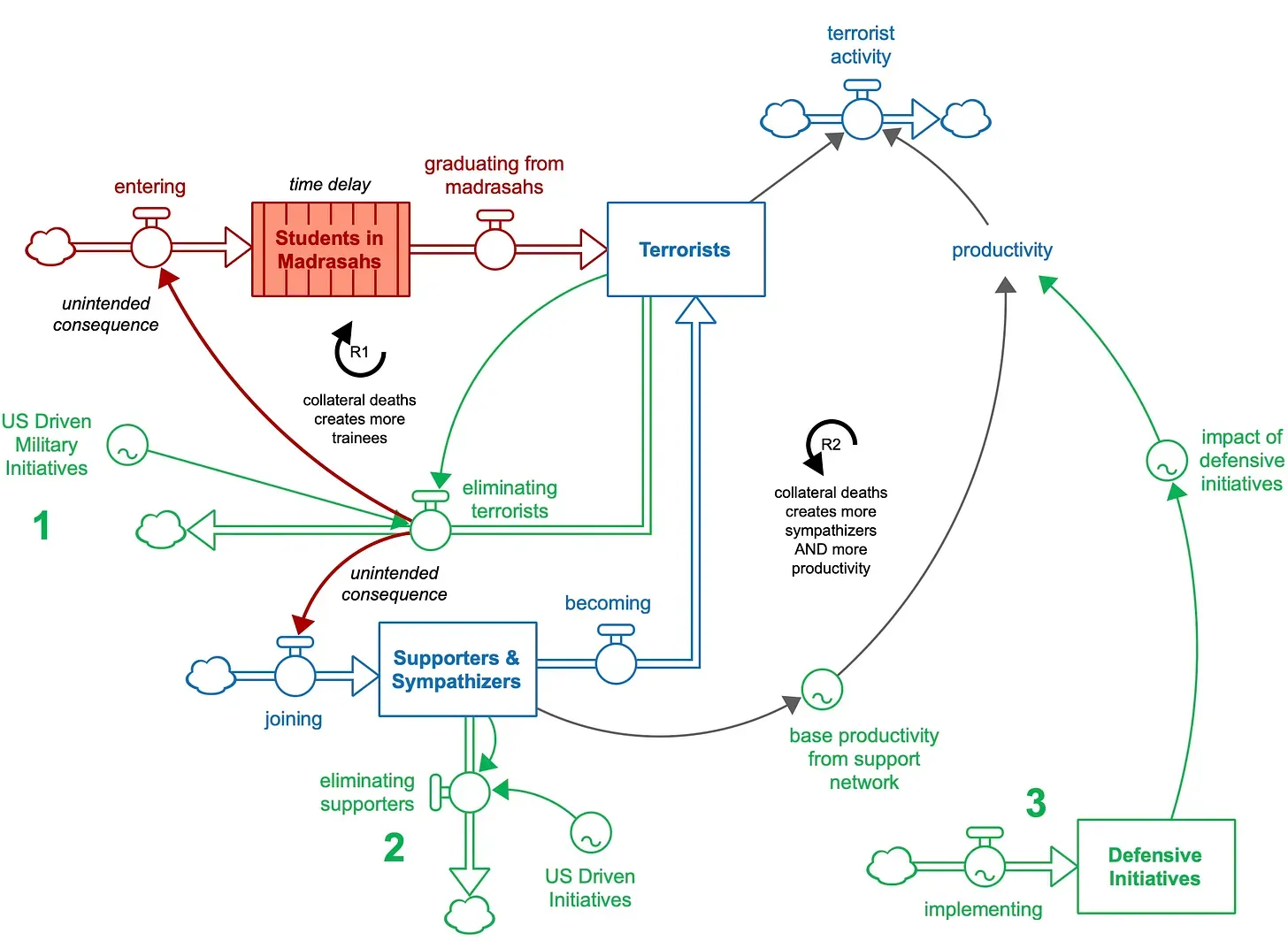

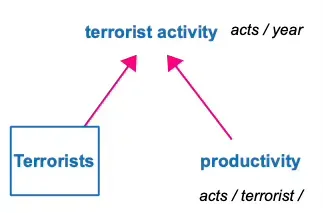

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.

LINEAR Thinking would suggest that an intervention that kills terrorists would work to reduce terrorist activity. However, by applying FEEDBACK LOOP Thinking we can see it will likely kill people who are not terrorists; this will motivate more potential terrorists to enroll in terrorist organizations and eventually be trained to commit acts. This would create a nasty reinforcing feedback loop (R1) known as a vicious cycle.